For several years, I’ve learned about the growing threat of legionella bacteria – the cause of Legionnaires’ Disease – from some of the nation’s top experts. I’ve immersed myself professionally in this issue and have read continuously about the risks, and the techniques and technologies brought to bear against these amazingly resilient pathogens.

But it wasn’t until a close relative came in contact with the bacteria within a hospital that the impact of this threat hit home. There for chemotherapy, she was exposed to the bacteria at the worst time of her life, when her biological defenses were down.

As her advocate, I found myself immersed in the battle for her life. I spoke with oncologists, hospital administrators, lawyers, infection control professionals and members of the state health department. New information was pouring in, ultimately to reveal the immense scope of this problem.

The incidence of Legionnaires’ Disease has increased by 550 percent or more in the last 15 years. Even the very best healthcare facilities must be vigilant to reduce the threat of infection from this potentially deadly form of pneumonia. Routine testing of domestic water systems is enormously important. And, of course, prevention and treatment – essentially, germ warfare – is imperative when facility managers and infection control specialists battle this virulent pathogen.

Hospitals and nursing homes usually serve the populations at highest risk for Legionnaires’ Disease. These include older people and those who have certain risk factors, such as being a current or former smoker, having a chronic disease, or having a weakened immune system – precisely what happens during chemotherapy.

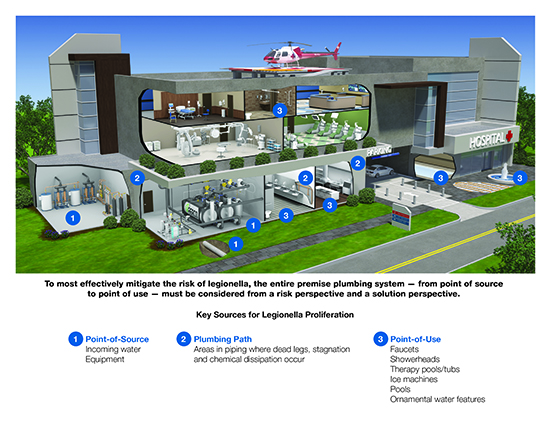

Healthcare facilities typically have large and complex water systems that can become the ideal host for legionella growth, and the spawning of other opportunistic waterborne pathogens.

Proactive hospital/healthcare facility managers have found that routine testing of water samples is very helpful. It’s not only a form of patient and healthcare professional advocacy, it’s smart business: Testing may become the lead source of protection against exposure within the facility (staff and patients alike), possible litigation and bad press coverage.

One way to look at it is this: Pay for prevention now, or pay for the consequences later. Experience and good advice agree that it’s far less invasive and costly to proactively work toward prevention of exposure to legionella bacteria than it is to reactively fight waterborne pathogens once they’ve inundated a facility’s waterways.

How often to test? Although industry officials appear to still be deciding this measure, most agree that multiple testing locations is best, and that if 30 percent or more of the tests come back positive, then action must be taken.

Multiple barriers

The world’s leading experts (and I) all agree that if you haven’t already taken the threat seriously, and even if you have, a multibarrier approach is the only way to effectively reduce the threat of Legionnaires’ Disease.

Bring everyone to the table: engineers, the facilities team, infection control and administrators, the local health department and the CDC. These are the professionals who need to turn their attention and expertise to meet the growing threat.

Of course, with all of this expertise on tap, don’t forget the reason why you’ve combined forces: protecting a potential victim or patient. Ask how they could come in contact with legionella at the facility; build your plan around that.

The facility’s team needs to consider multiple solutions from point of entry, along the premise plumbing path and to the point of use. Legionella and other waterborne pathogens are resilient. They can re-populate and find food sources throughout a facility’s plumbing infrastructure.

Full arsenal

There are many weapons in the war against these pathogens; some are effective, some not so – but none are completely effective, individually.

Essentially, there are five key “weapon systems” brought to bear against waterborne pathogens within premise plumbing/domestic water systems within facilities:

- Heat

- UV

- Scale control

- Chemical water treatment

- Point-of-entry ultra-filtration and point-of-use filtration

For maximum effect, all five are brought to bear.

Facility managers must determine which solutions are best for their buildings. Because every building is different (age of the structure, complexity of system, amount of dead legs, extent of renovation/additions, etc.), each facility should have a tailored solution.

There are, however, three solutions that should be considered for all facilities:

• Controlling temperature through a digital mixing station. Experts have proven that controlling water temperature – above 140 degrees for storage, with proper reduction of temperatures for points of use – has become the chief weapons system in the battle against Legionnaires Disease.

• Using ultraviolet light at points of entry. Studies have shown that UV is effective as a part of an overall solution, and it is rather inexpensive to implement.

• Controlling scale not only increases the lifetime of equipment (heat transfer surfaces are protected), but it can reduce food available for legionella to grow and also hide.

Design considerations

Plumbing systems can be complicated, especially within a hospital. A majority of hospitals are older structures that have been expanded and renovated multiple times. This increases the complexity of water systems.

Some design methods include continuous recirculation of domestic hot water; high water temperature is maintained throughout the main waterway, with mixing valves at all points of use.

Yet, there are still challenges. First, consider that many large facility domestic water systems can contain many thousands of gallons of water (U.S. hospitals are water hogs, using an average of 570 gallons of water per staffed bed). That’s a lot of water.

Second, consider that as water moves away from heat sources where temperatures may be sufficient to prevent germ growth, those large pipelines may cool domestic hot water to the ideal temperature ranges for waterborne pathogens.

Finally, consider, how ubiquitous biofilm is within those piped waterways. As microbes grow, they attach themselves to wetted surfaces in water distribution systems. They protect themselves from disinfecting agents, and heat, by forming biofilm.

A biofilm contains a group of bacteria enveloped within a polymeric slime that ensures adhesion to the pipe surface – and a nice, soft place for resilient microbes to grow and prosper.

The biofilm also contains the food for bacterial growth, adding substantially to the importance of this challenge.

Even water in new facilities has this risk. Consider how long water has been in the building prior to opening the building for operation. Typically, that’s many months where it sits, becoming stagnant – a perfect home for biofilm buildup and bacterial growth.

Sadly, many hospitals have opened only to be confronted with numerous legionella cases, the source being the water that was introduced to the piped systems long before the first patient walked in the door. Proper disinfection and flushing must happen to help combat this problem.

Battling biofilm

Biofilm isn’t just a place for germs to hide and seek protection. It’s their buffet. So to attack the biofilm makes real sense. A few design choices in the plumbing system can help:

• Keep the water flowing.

Continuous recirculation reduces biofilm because sitting water becomes stagnant and promotes its growth. On the other hand, continuously moving water doesn’t stagnate. Make sure the flow is sufficient; in recent years the industry has promoted low flow to conserve water. While this is a worthy effort, it’s not as effective in battling waterborne pathogens.

Another related facet in combating biofilm is to make sure that the pipe is sized correctly. Don’t oversize! Oversized pipe not only affects flow (slowing it down and reducing helpful turbulence within the waterways), but also increases the surface area for germ-harboring biofilm to grow.

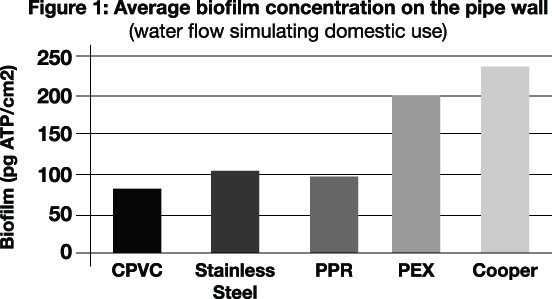

Also, consider the piping material. In general, smooth piping doesn’t harbor as much biofilm as rougher, more porous material. Researchers have studied biofilm growth on different types of materials, with variables that also include factors such as water flow and temperature.

• Avoid dead legs/chemical treatment.

In existing buildings there isn’t much that can be done about piping dead legs if they’re already present; these low-flow/no-flow areas provide safe harbor/refuge areas for legionella and other pathogens. So, if there are dead legs within a building’s piped infrastructure, solutions must be considered.

First, consider a disinfectant such as chlorine or chloramine, but keep in mind that they dissipate as the water travels through the plumbing system. Copper silver may be a good choice because it resists dissipation between POE and POU.

Also, be sure to consider POU options such as filters that can be used as a last line of defense.

• Mitigate risk through tech.

Technology can play a significant role in mitigating the risk of legionella and maintaining a water management plan.

Utilizing sensors to monitor flow, temperature, and disinfectant levels can alert managers to potential problems. Digital mixing stations allow for precise water temperature control and the ability to purge systems should an outbreak occur.

As part of the water management plan required by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare, hospital managers are required to keep records of how they’re mitigating legionella risk.

Digital mixing stations, sensors and other technologies easily allow hospital managers to collect and record data such as water temperature. Most connect directly to a BAS system and some have abilities to control features off-campus or at a minimum be warned if something is out of range.

• Finally, don’t forget about the drains

Too often, serious consideration to waterborne pathogens often disregards the presence and role of drains. It’s easy to think that since the water is essentially leaving the path to a person then it shouldn’t be harmful, but it’s not so.

Bacteria is prolific in the drainage parts of a sink. Not only is it there, but it has been shown to “climb” out of the drain and then potentially come in contact with a person. So, the next time you examine the plumbing leading up to the faucet, take a close look at the drain, too.