While I’m a bit embarrassed to admit it, I didn’t learn how to read a geotechnical report until more than a decade into my career. Before that, a structural engineer usually took the lead in reading and interpreting the report and discussing the implications with me.

It wasn’t until I got involved in project management that one of those structural engineers sat with me several times and went through a report, showing me what to look for and teaching me what everything in it meant. It was then that I realized how critically important the information in the report is to a project.

While geotechnical reports are of the most interest and importance to structural and civil engineers, plumbing engineers also need to read and understand them. The reports contain critical information about site soil and water table conditions, both of which impact building structure and below-grade plumbing systems.

If these conditions are less than ideal and you do not adequately design for them, the results can be disastrous for a building and costly to fix. High water tables can cause floor slab cracking and water infiltration without adequate subsoil drainage, and expansive soils can cause below-grade plumbing systems to heave and buckle without adequate isolation or protection.

To those reading them for the first time, geotechnical reports can often seem long-winded and vague. A primary reason for this is that geotechnical engineering is a high-risk discipline — errors and omissions in reports can result in structural catastrophes, property loss, injury and death, as well as the associated lawsuits. All this considered, there are several key points of interest in them that plumbing engineers should focus on.

What to look for and where

Geotechnical reports can span more than 100 pages, depending on the project’s scope, contain language that plumbing engineers aren’t familiar with, and do not always contain clear direction on what to do with the information. However, as you read more of these reports, you’ll discover that many follow a pattern in their contents. If you go into one of these reports knowing what you need from it, you can focus on where to look.

Most reports begin with a letter from the geotechnical engineer who oversaw it, a description of the scope of services the firm was hired for, and the information and a summary of the report’s recommendations. The latter two items are worth reading as they give clues about what you’ll find in the rest of the report and, sometimes more importantly, what you won’t find.

The information following the introduction gets denser, providing a detailed description of the project as the geotechnical engineer understands it, site conditions encountered during the study, profiles of subsurface soils and groundwater, seismic design parameters, and a general site overview based on the firm’s subsurface exploration and soil borings.

Following these sections, the report typically discusses recommendations for earthwork and site preparation, drainage, suitable foundation types, floor slabs, and frost considerations.

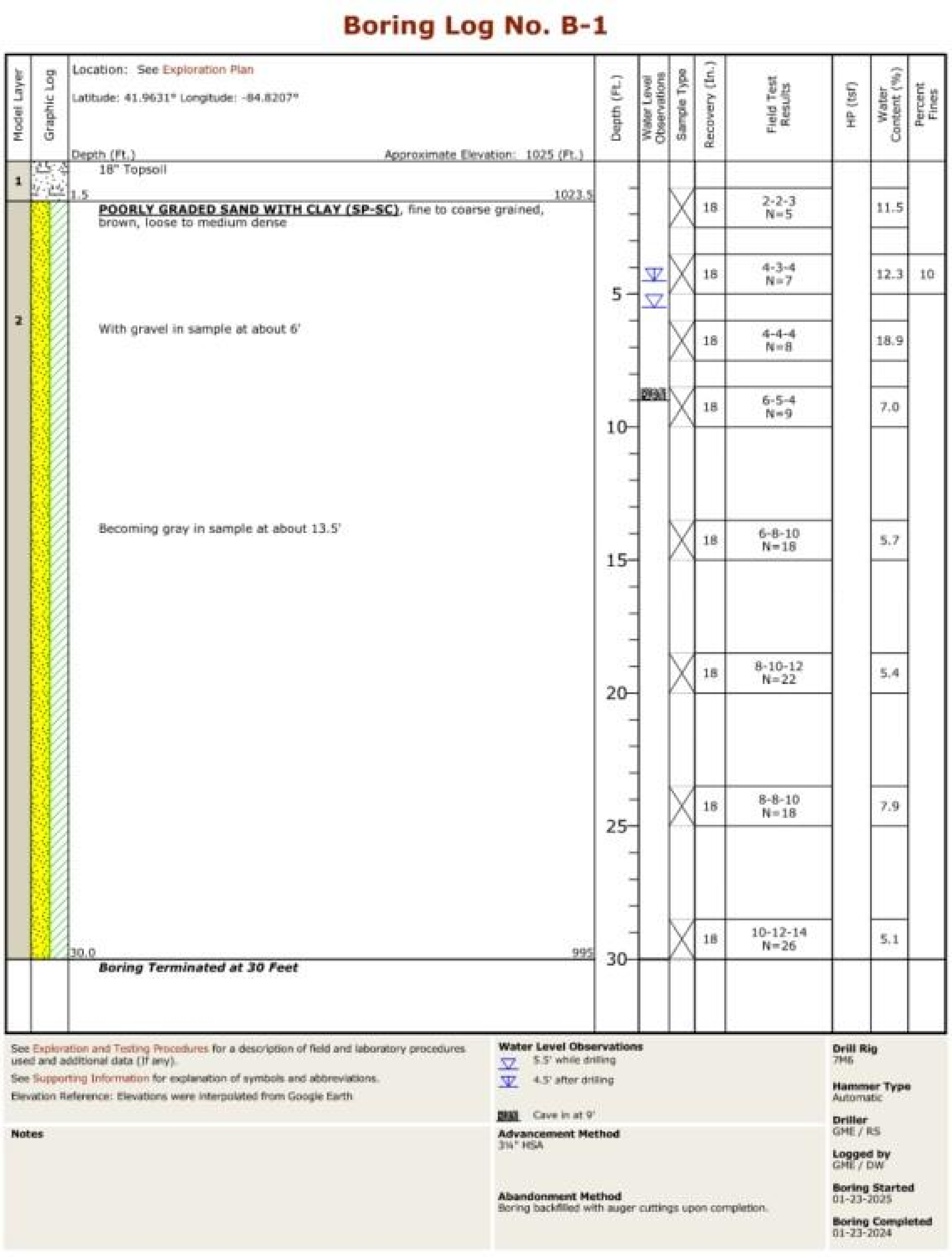

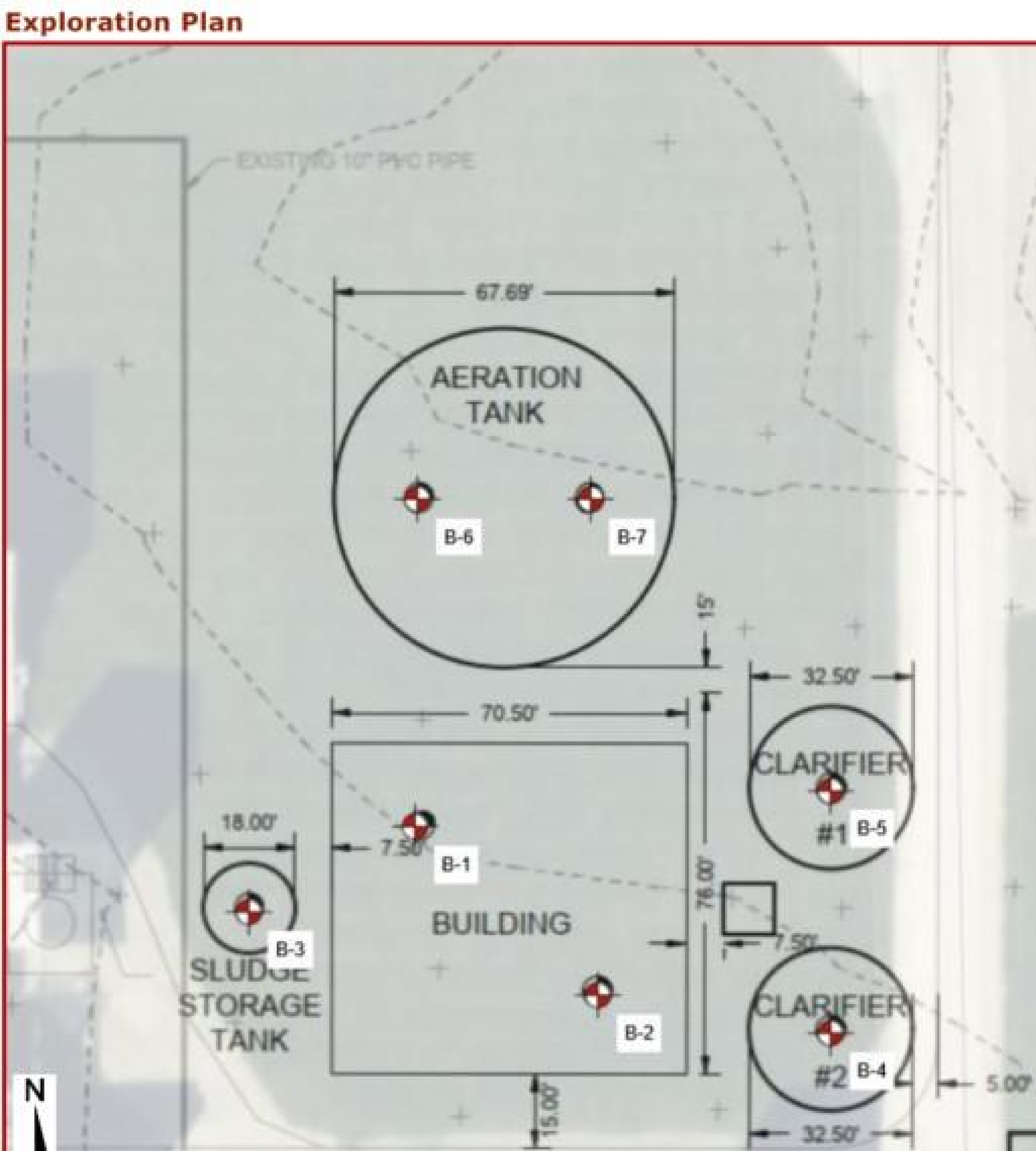

Finally, reports typically conclude with general comments that incorporate risk management language and appendices that display soil boring maps, soil profiles at each boring location and testing methods.

Plumbing engineers should focus on sections containing information about groundwater conditions and soil types at specific depths, particularly subsurface profiles and groundwater conditions, native soil types and profiles, and recommendations for subsoil drainage and soil improvement.

Reviewing the soil boring maps and subsurface profiles at each location is also a good idea. All this material will help you make informed decisions about mitigating site conditions that could damage the building and your systems. If not addressed in your plumbing design, high groundwater can cause hydrostatic pressure on foundations and floor slabs, causing them to crack and water to infiltrate the building. Additionally, certain soil types are prone to expansion when saturated and can cause underground pipe to heave and crack.

• Groundwater

Studying the language around groundwater conditions usually gives the best indicator of whether a subsoil drainage system is needed. Some geotechnical engineers may be hesitant to offer recommendations on groundwater mitigation in their reports, instead leaving the determination to you. The most thorough ones clearly state these recommendations and give details on where the water table needs to be below the structure and floor slabs to avoid issues.

If groundwater is a potential concern for a given site, make sure the lead architect or owner includes a groundwater assessment and recommendations in the geotechnical request for proposal’s (RFP) scope before hiring the geotechnical engineer. Groundwater mitigation recommendations are usually not provided by default, thus they need to be included in the geotechnical RFP during solicitation.

• Groundwater conditions

The presence of shallow groundwater, combined with primarily sandy soils, has the potential to negatively impact construction activities, especially for the overexcavation and replacement of weak soils. Temporary and permanent dewatering systems may be required to maintain the groundwater table at approximately 2 feet below the bottom of the planned footings during and after construction activities are completed.

Reviewing the soil boring map and soil profiles at each boring location is also a valuable exercise for understanding the groundwater conditions and elevations, which are not always consistent throughout a site. Some areas may require subsoil drainage, while others can be left alone.

Where the building sits is also a factor. Take note of what elevation groundwater was encountered at each soil boring, determine where it sits relative to building floor slabs, structure and elevator pits, and see if there is enough clearance between them to meet the report’s recommendations.

Remember that even if groundwater levels are low enough to eliminate the need for subsoil drainage, problems can still arise if you have underground piping, sumps or interceptors with unusually deep inverts. In such cases, you might need to find ways to isolate these from the groundwater.

• Expansive soils

In addition to groundwater conditions, site soil types are another important factor to consider, as specified in the report, particularly if the native soils are expansive. Expansive soils swell when they become wet, contract when they dry, and tend to be composed of clay minerals. These soils can damage underground pipe (and structures) as they expand and contract.

If expansive soils are present, the geotechnical report typically states this in the geotechnical overview and discusses them more in the earthwork section. These sections may also provide recommendations on how to address them. As with determining groundwater conditions, review the soil boring map and soil profiles throughout the site to identify areas where these conditions might be encountered.

Challenges and solutions

High groundwater and expansive soils present design challenges; there are several ways to address them, some of which may be beyond your control. Geotechnical reports often include suggestions for these issues, but some reports are vague enough that you might be unsure of the next steps. In such cases, it is always wise to contact the geotechnical engineer for recommendations and clarifications as needed.

• Addressing high groundwater

High groundwater is typically only a concern for buildings with basements; however, the water table may be high enough to affect slab-on-grade buildings as well. Even in these cases, a subsoil drainage system isn’t always needed to mitigate it. Sometimes, an easier solution, usually led by the civil engineer, is to build up the site with well-draining soils so the building sits at a safe elevation above groundwater.

If you’re in a high groundwater situation, it’s worth considering whether it can be resolved this way; however, the answer often depends on the cost of the site improvements. While it can be a riskier solution, a subsoil drainage system is often easier on the project budget.

If a subsoil drainage system is inevitable, several coordination exercises are involved in designing it correctly. The first exercise is to review the elevations of all below-grade building elements — foundations, elevator pits, floor slabs, piping and other utilities — and determine which of them come within an unacceptable distance to the water table. Again, the geotechnical report should specify this distance, but consult the geotechnical engineer if it does not.

The second exercise involves collaborating with the architect to understand the building’s waterproofing strategy and identify areas that may be susceptible to water infiltration. The third exercise is to work with the structural engineer to determine if the water table will produce unacceptable hydrostatic pressures on the foundation, elevator pits or floor slab.

The subsoil drainage system you design and what it protects depends on the results from these exercises. For example, groundwater may only be high enough to encroach on elevator pits, but water infiltration may not be a concern if they are adequately waterproofed. Elevator pit structures are often dense enough to overcome groundwater hydrostatic pressures, in which case a subsoil drainage system may not be necessary for them.

Another example is where the groundwater may encroach on the building’s foundations at the perimeter, but not elsewhere. In these cases, the geotechnical or structural engineer may recommend a subsoil drainage system around the building on the exterior, interior or both. Groundwater may also encroach on floor slabs, which can cause slab shifting and cracking. These situations may call for a gridded subsoil drainage system throughout the building footprint to relieve the hydrostatic pressures on the floor.

• Addressing expansive soils

I’ve found that expansive soils aren’t as common as high water tables, but they are no less problematic. Expansive soils can damage underground piping and other utilities when they shrink and swell with moisture changes. In these situations, the piping and utilities must be isolated from the expansive soils.

The easiest way to do this, but not always the most cost-effective, is to remove the expansive soils from the site. Removal involves excavating and hauling problematic soils off the site and replacing them with fill that is suitable for the building structure and any underground elements.

The decision to do this often lies with the civil engineer and those managing the project budget. If removing the expansive soils isn’t an option due to design or cost constraints, the next alternative is to build a crawlspace under the structure where the piping and other utilities are accessible and not buried in the soil. This option is often convenient for maintenance staff when accessing below-grade piping; however, crawlspaces become increasingly prohibitive as building floor areas increase.

If a crawlspace isn’t an option, piping and other utilities should be installed in utility tunnels or void forms that provide them with separate, isolated spaces away from the surrounding soils. Many manufactured solutions are available for this on the market but utility tunnels may be field-built as well.

Design coordination

A geotechnical report should be obtained for every new building, even if it is an addition to an existing one. Geotechnical engineering is a high-risk discipline and an error or omission in a report can be catastrophic. The implications for plumbing systems are severe enough, but those to the building structure can be far worse.

For these reasons, it is best that the building owner — not your firm — be the one to hire the geotechnical engineer, as it transfers the risk away from you. If you are in a position on your project team to influence this decision, be sure to push for it. Ask for geotechnical reports early in the project, as they can have sizeable implications on design and construction costs.

When you receive a geotechnical report, take the time to read and understand its implications on your plumbing systems. Verify your understanding of these implications with your civil and structural engineers to ensure they are aligned. These disciplines are often more familiar with these reports and can help clarify vague areas. Speak to the geotechnical engineer who drafted the report directly if anything is unclear, especially recommendations on resolving site issues that affect you.

Remember that the geotechnical engineer was hired not only to write a report but also guide the full design team in decisions around the site’s subsurface. Do not hesitate to reach out to them if you have any questions regarding plumbing systems. They have been hired to help you.

If geotechnical conditions pose challenges for your systems and require mitigation, be sure to discuss your proposed solutions with the project team. Sometimes, you’ll get stuck resolving these issues within your discipline, but at other times, someone else may suggest a broader solution — such as elevating a building above groundwater or replacing problematic soils — that benefits the entire team and project while reducing risk for everyone.