The digitization of channels is upon us. The most recent evidence of the scope of the change is found on Black Friday where online sales are expected to top physical store sales. This trend shows no signs of reversing and brick and mortar retail is a model of business in decline. Despite acclaimed differences by wholesaler execs on the variances in retail versus wholesale, our research finds that the digital journey of distributors at large will, most likely, parallel that of retailers including:

- Attempts to take the full-service model online with little success

- Building out of successful, competitive e-commerce software platforms with initial success, but fading performance

- Rationalization that the existing business model and culture works well online

- Underestimation of the scope of change of the existing organization to compete online including streamlining of sales and branch locations and cost of complexity as an ongoing barrier to online success

- Rationalization of share gain by new models of business into the traditional wholesale-served space

Several respected research studies in 2016/17 of both end users and distributors found that distributors are losing online sales after initial success. The observation is that distributors invest significant sums in software and gain online sales, then begin a slow decline. Picking up these sales is a group of manufacturer-direct, new online entities, and a small sliver of wholesalers who have pushed the envelope of the old business model. Traditional distribution is in decline despite some recent year-over-year sales growth due to a full-employment economy. The goal of this series is to examine the why, what and how for traditional distributors to move from loss to gain as their markets digitize.

The decline of full-service distribution

The fundamental issue of non-competitiveness of full-service distribution is inefficiency in operating structure as measured in cost-to-serve. As the number of distributors began to decline in the 1990s and consolidation drove out back door costs, the cost to serve began to increase.

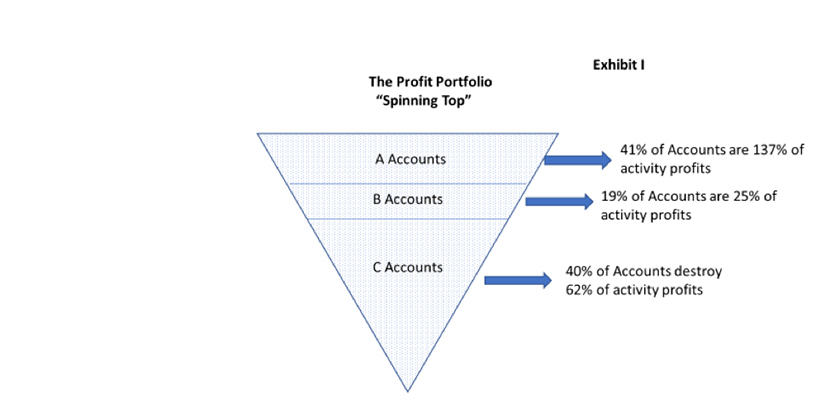

This cost-to-serve problem was not visible in the annual earnings of distributors, but was visible in the distribution of activity profits of the customer. The issue, in Exhibit 1 (above), is that fewer and fewer accounts fund the operating profit before tax of the wholesaler. As distributors move further into the value chain to differentiate their offerings, they engage services and sellers extend the service promise often without a tangible increase in margin dollars. This is exacerbated and accelerated by compensation systems that reward on margin dollars on product sales, not on activity profits, which would include the cost-to-serve. As industries and product applications become more mature, sellers, to maintain an advantage, differentiate services by the account, by the application, by the invoice, and even by the line. The result is a dependency on a small portion of customer accounts (A) that are the vast majority of profits (137 percent of activity profits), followed by (B) accounts that are nominal profits (25 percent of activity profits) and (C) accounts (40 percent of accounts) that destroy 62 percent of activity profits. The forward momentum of maintaining or increasing profits in this model relies on:

- Trying to limit services to B and C accounts while increasing prices

- Detailed/increasingly smaller pricing actions to A accounts that “flies under the radar”

- Increased demand for vendor rebates, individually and through co-operatives, or special pricing agreements supported by key vendors

- Cutting accounting period expenses wherever one can and often conflicting with long-term investments in market strategy

- Trying to drive scale and scope economies through acquisition

- Management of countless data points in customer based analytics to eke out decreasing increments of profit

As the firm grows, however, the service promise balloons and so does complexity and inefficiency. Distributor executives and managers become increasingly short-term in their activities and their work to grow profit is akin to keeping a spinning top from slowing down. Profitability gains are incremental with shortened time frames, long-term strategies are increasingly difficult to realize, over-servicing of marginal or negative activity accounts increases, and pricing gains become more difficult as online pricing exposes non-competitive offers. The conglomeration of different wholesaler businesses, under one banner, is part of the problem also unless management uses digital technology to streamline the firm and alleviate the world of the spinning top. It is of note that the advantages of consolidation become a trap as the diversity of markets and their needs grows expenses faster than margin dollars. Called diseconomies of scale and scope, these expenses are most evident when new models of business appear and capture share with a reduced price and lessened service promise. Supporting this observation is that distribution has not, historically, scaled well as operating expenses, more often than not, quickly rise to support volume.

A new world, a more efficient

business, an easier to manage game

The advent of e-commerce in distribution began in earnest in the late 1990s in distribution. In these early years, however, the software to successfully engage in B2B commerce was mostly self-programmed and did not allow for a full self-serve experience. Starting a few years after the Great Recession and benchmarked by Grainger’s announcement of 300 new technology jobs in Chicago in 2013, B2B software became specialized and a software bundle emerged to allow customers to self-serve and sparingly use the services of inside and outside sales staff. The software bundle consists of off-the-shelf transaction software, PIM, faceted search, punch-out, and online quotation/special pricing. Our research finds that distributors with this bundle outsell online competition by a factor of 3x.

While many distributors are building out the software bundle, other companies have found online organic growth. This includes:

- Manufacturers who are increasingly going direct. Many manufacturing firms have found that the wholesale channel with growing special pricing agreements and increased demands for vendor rebates to be less profitable than taking sales direct.

- New business models that are made for online commerce including firms such as Amazon, Zoro Tool, and Sustainable Supply.

- 5 percent or so of traditional distributors who use technology to streamline/change redundant parts of the value chain while creating new online models.

The upshot is research that confirms distributors, at large, are losing in the high-growth online channel. Many distributors have trouble in seeing a loss from online competition. This is a function of the newness of the online channel, the recent made for B2B software bundle, low share of e-commerce sales where some 15 percent of volume is online, and a high growth economy. But the research, new online model growth, and manufacturer direct success tells a different story of overall decline in e-commerce sales through full-service distributors.

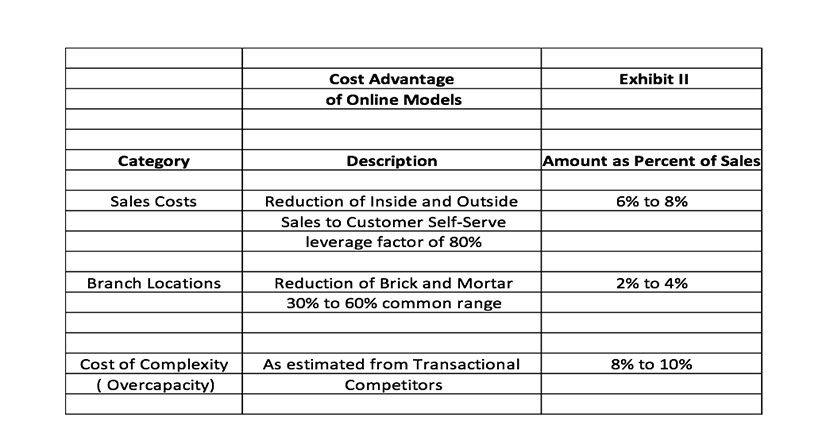

Online entities have a significant cost and ease of management over managers of the spinning top variety. Their cost advantage is significant as estimated in Exhibit 2 (above). From the exhibit, we’ve listed Cost Category, Description, and Common Range as a percent of sales. In the online, self-serve world, the customer has limited requirement of assistance as a predominance of products are commodities that the customer is well-familiar with. Leveraging (reduction) of the sales effort by 80 percent gives a common range of 6 percent to 8 percent of sales as a cost advantage. Branch locations in the online world are greatly reduced. Benchmarks are Grainger, which has significantly reduced physical branches and made-for online models which operate out of a handful of locations. Reductions of 30 percent to 60 percent over full-service firms gives a cost advantage of 2 percent to 4 percent of sales. Finally, because of the varying and growing service promise of the wholesale firm, there is a constant need for over-capacity in operations and to maintain service quality. We are aided in this effort by BPM (Business Process Management) efforts in distribution firms and research on Transactional distributors (new age entities that use e-commerce and take cost advantage to market in the form of price). The overcapacity for full-service firms is a common range of 25 percent to 40 percent to maintain service quality and maintain the growing and ever-changing service promise. The upshot is that the over-capacity cost is 8 percent to 10 percent of sales.

The total of these cost advantages is 16 percent to 22 percent of sales and washes with our research of Transactional distributors who can reduce price by 10 percent over full-service distribution and put 8 percent or more of sales to the operating profit line.

Hence, the current direction of full-service distribution with incongruences of compensation and service promise, growing scale and scope diseconomies, and cost disadvantage vs. online competition, create a firm that will have a very difficult time competing online.

Online competitors don’t have to worry nearly as much about an expanding service promise, over-capacity to maintain service quality, and redundant inventory locations. Their models, value proposition, and technology advantage allows them to slice apart the full-service value proposition. Managing the new online firm is less of an issue than the need to get new customers who understand and value a non-traditional supplier who uses technology to create a new value stream.

This article is part one of a three-part series. In our next installment, we’ll go over product/market dynamics and the need for the full-service firm to build out technology and where/how to use it to compete in the digital environment.