Sustainable solutions often revolve around the idea of maximizing available resources. These may include climate and other external resources or may be altogether independent of location, depending on the mix of program types.

Climate-based solutions frequently target reduced energy use. Systems that always reject heat, such as data centers, can easily operate at a higher efficiency in a heating dominated climate; however, if they do not consider energy recovery in the solution, they fall short of their potential.

Sometimes the building programs themselves, combined with the local climate, can fill this void without the need for external resources. In laboratory buildings, for example, energy use is driven primarily by the conditioning of outside air; if located in a heating dominated climate, it’s driven by heating energy. If the same building includes a significant data center or excess process cooling, there lies potential to repurpose waste heat to efficiently generate reduced energy heating while reducing cooling demands for the associated program.

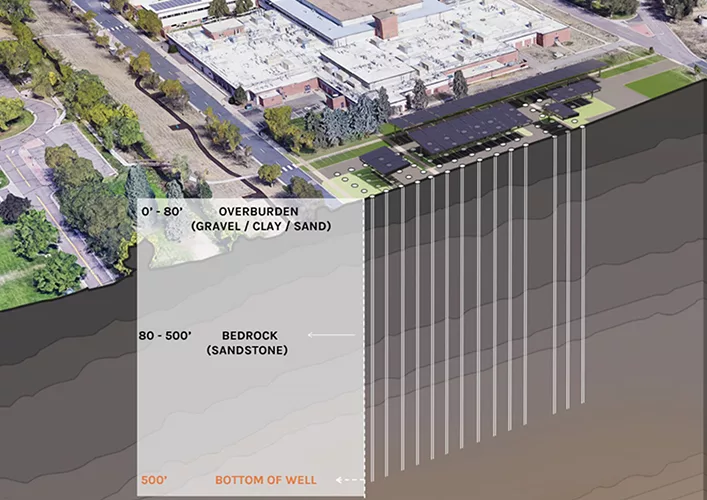

Geothermal uses the ground as a heat sink, either to store or extract heat. In summer months, heat from the building warms a geothermal field, which is comprised of a network of horizontal or vertical ground loops together with ground-source heat pumps (GSHPs). Over the course of the summer waste heat elevates ground temperatures in the geothermal field, which can then be extracted in winter to help heat the building.

While the temperatures extracted from the ground are not sufficient to provide cooling or heating on their own, the use of GSHPs (water-source heat pumps) enhance these temperatures while lowering energy use to provide heating and cooling to the building (see Figure 1).

An underlying assumption for geothermal systems is that the total heating and cooling demands over the course of the year are approximately the same and neutralize each other. Too much of one system or the other can saturate the ground temperatures, leading to either warmer or cooler ground temperatures over time and limiting the effectiveness of these systems. For this reason, it is more common to see geothermal systems applied in more balanced climate zones.

Using climate zones to inform geothermal applications

The 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC)and the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) have established climate zones to assist engineers and others in understanding the characteristics of their climate. These climate zones have numeric designations ranging from 0 (extremely hot) to 4 (mixed) to 8 (subarctic/arctic) in terms of their thermal characteristics, as shown in Figure 2.

Each climate zone also includes additional identifiers to describe the moisture characteristics of climates, ranging from A (humid) to B (dry) to C (marine or coastal). Together with their numeric designations, climate zones help define the characteristics of a given location, which can in turn assist in identifying potential system solutions. Phoenix, Arizona, for example, is climate zone 2B (hot, dry) while Chicago, Illinois, is climate zone 5A (cool, humid).

Each climate zone also includes additional identifiers to describe the moisture characteristics of climates, ranging from A (humid) to B (dry) to C (marine or coastal). Together with their numeric designations, climate zones help define the characteristics of a given location, which can in turn assist in identifying potential system solutions. Phoenix, Arizona, for example, is climate zone 2B (hot, dry) while Chicago, Illinois, is climate zone 5A (cool, humid).

As noted earlier, geothermal systems prefer more balanced climate regions. Assuming potential geothermal systems supporting the heating and cooling of the building, then the ideal application is climate zone 4.

It is common to see geothermal systems also applied in climate zones 3 and 5 as well, though energy modeling is recommended to validate the approach. Building programs with consistent, reliable waste heat correctly applied in heating dominated climates (zone 5 and above) allow geothermal systems to operate closer to a zone 4 performance.

Application of heat pumps for geothermal heat exchange

GSHPs use a hydronic loop to transfer heat between the building systems to the ground source. The heat pump then boosts the temperatures of the hydronic loop to support heating or cooling in the building systems.

Smaller systems that one might find in residential applications may take that heating and cooling directly to a refrigerant coil in an indoor unit to condition the building (ground-source to air).

Larger systems such as those found in commercial applications use ground-source loops to support heating and chilled water systems in the building (ground-source to water). Configured correctly, these larger ground-source systems can also support simultaneous heating and cooling within the building.

Given the more balanced climate and depending on the building program, there may be significant periods during the year where all or a portion of the heating and cooling loads balance out, independent of the geothermal loop contribution.

Energy modeling is a useful tool to evaluate the viability of geothermal and other sustainable solutions. By studying the heating and cooling contributions of different systems over the course of the year, we can examine the building load profile to confirm its application to geothermal.

If geothermal was considered for climate zone 3 or 5, the output from the energy model would be combined with geothermal modeling software to validate the size of the geothermal field needed to support this application (see Figure 3).

Application of geothermal to building systems

With smaller ground-source-to-air heat pump systems, the geothermal loop is piped individually to each heat pump zone. Depending on the time of year, zone orientation, time of day, and other factors, individual heat pump zones may operate in heating or cooling mode. While simultaneous heating and cooling is not an option, any simultaneous heating and cooling from different heat pump zones will temper the water sent back to the geothermal loop and help extend the capacity of that loop to support building systems over the course of the year.

Larger GSHP systems allow for increased flexibility in the mechanical systems design. The heating and chilled water produced by these systems support a variety of approaches and allow for flexibility in building programs over time. Selecting system solutions that use cooler heating temperatures and warmer cooling temperatures can significantly increase heating and cooling energy efficiency.

When designing in heating-dominated climates, it is common to find scenarios where the geothermal field supports operations for over 95% of the year but begins falling short of capacity in peak heating periods. In such cases, evaluate the use of supplemental heating sources for these peak periods in lieu of moving away from geothermal.

We often find that any energy penalty of the supplemental source has minimal impact on increased energy efficiencies given the limited number of operating hours.

Application of geothermal to other systems

The application of geothermal is not limited to building heating and cooling systems and may be applied to other systems within the building. Heat pump water heaters (HPWHs) reject cooling to a geothermal system year-round but are often at a much smaller scale than that of the building heating and cooling systems. Due to their smaller size, these systems often have minimal impact on the sizing of the geothermal field; however, they can benefit from the increased energy efficiency of the geothermal application.

Laboratory process cooling or water-cooled air compressors are another application that can be applied to a geothermal system. Both systems reject heating year-round, but like the HPWHs they are often at a much smaller scale than the building heating and cooling loads. Energy and geothermal modeling are recommended to confirm geothermal field sizing and improvements to energy efficiency.

Geothermal systems can significantly improve building energy efficiency by using the mass of the ground below to store and extract energy from over the course of the year. Geothermal’s ability to store energy helps eliminate the waste common in traditional building systems that discard heat when cooling while using a separate energy source for heating.

Geothermal systems also enable energy efficient operations for other systems as well. Their application, however, presumes a relatively balanced heating and cooling load profile over the course of the year.

Note that geothermal field designers have multiple options for bore-field designs, allowing a smaller site area for geothermal to support an increased building load. Therefore, even when the available site area for geothermal is limited, we recommend conducting a preliminary evaluation to confirm viability.

The goal of geothermal and other sustainable solutions is to leverage the heating and cooling loads of the building to reduce waste. A properly designed geothermal system also increases the building’s resilience in times of system outages, as well as reducing the use of water for mechanical cooling and power generation.

Robert Thompson, PE, is a mechanical engineer and senior principal at SmithGroup. He actively supports the Science + Technology Studio in the Phoenix office as well as Mission Critical project across the United States. He also partners with the SmithGroup’s Integrated, Multidisciplinary, Performance Analytics Climate-Impact Team (IMPACT) with a focus on energy efficiency and sustainable project solutions.