Fire sprinkler and standpipe systems are integral to the protection of buildings and the safety of the occupants within. An easily overlooked component of sprinkler and standpipe system design is drainage. Selecting proper drain locations and types is essential for facilitating system testing, maintenance, repair and modifications.

Careful coordination of drains is required among fire protection engineers, plumbing engineers and architects to ensure that water being discharged from these systems is diverted away from the building, preventing water damage and delayed response of fire suppression systems.

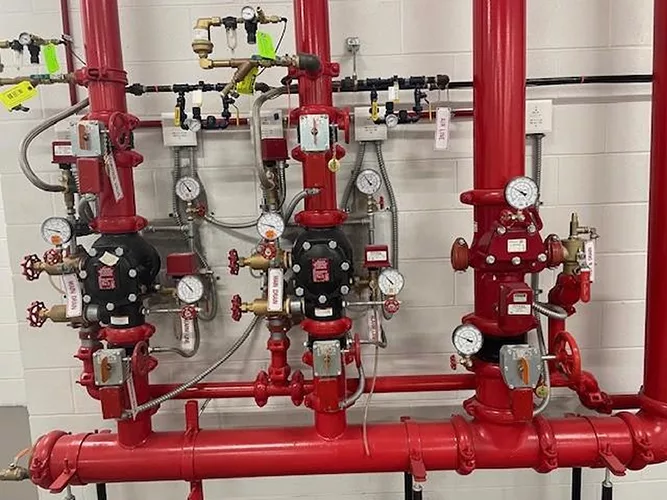

When designing fire protection systems for a building, the locations of sprinkler and standpipe risers, zone control assemblies, isolation valves and other fire suppression system equipment are determined and coordinated. Once this equipment is located, the associated drainage components should be coordinated.

Given their critical function, drains must be protected against various risks to ensure their reliability when needed. This column aims to provide an overview of the importance of sprinkler system drains and considerations when coordinating drainage with plumbing engineers during the planning and design phases of a project.

Nationally recognized codes and standards outline the basic requirements for the drainage of fire sprinkler and standpipe systems. NFPA 13, Standard for the Installation of Fire Sprinkler Systems, and NFPA 14, Standard for the Installation of Standpipe and Hose Systems, describe the associated components, sizing, location and installation requirements for sprinkler and standpipe system drains.

Sprinkler and standpipe system drainage should be discussed with architects and plumbing engineers early in the design process. Leaving drain coordination to the later phases of a project can lead to challenging design alterations to coordinate space for sprinkler, standpipe and plumbing drains with architectural features.

Understanding the types of drains necessary for a fire suppression system, along with the location and installation requirements of these drains, is essential for designing an effective fire suppression system and a well-coordinated building.

Why are drains necessary?

There are multiple reasons for draining a sprinkler system:

1. Repairs and maintenance. When a sprinkler system needs to be repaired due to corrosion, improper maintenance, physical damage or other similar circumstances, it is crucial to drain any water from the system prior to performing repairs to prevent water damage in the building.

2. System testing. Per NFPA 25, Standard for the Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems, all sprinkler systems must undergo a main drain test annually to determine if there have been any changes to the available water supply.

Pressure-reducing valves (PRVs) are required to be tested at five-year intervals to ensure their proper operation.

3. Modifications. When extending an existing sprinkler system or modifying it to cover a building addition or renovation, the system must be drained prior to the start of work.

All sprinkler systems will eventually need to be drained. It is important to make sure that these systems are designed in accordance with relevant codes and standards and can be effectively drained when required.

Main drain connections

When planning and designing a fire sprinkler system, it’s crucial to consider the drainage requirements for individual sprinkler zones and the system as a whole. NFPA 13 states that all parts of the sprinkler system have provisions for proper drainage. Similarly, NFPA 14 states that all standpipe systems be equipped with a main drain.

The main drain is the primary means for draining sprinkler systems within a building. Ideally, all piping should be routed so that the entire sprinkler system can be flushed via the main drain, found at the sprinkler system riser.

In multistory buildings, it is common practice to see sprinkler system zone control valves located in exit stairways at main or intermediate landings, with a shared drain riser running from the topmost zone control valve to a low point in the stairway. The size of the drain connection from each control valve to the drain riser, as specified by NFPA 13, is based on the size of the sprinkler main being drained.

When a shared drain riser is used, it must be one pipe size larger downstream of the main drain connection from the zone control valve.

Standpipes have similar drainage requirements to sprinkler systems. The standpipe main drain is sized based on the size of the standpipe riser and is required to discharge in a location that allows the drain valve to be fully opened without causing water damage. Where deemed acceptable by the authority having jurisdiction, the lowest hose valve connection can be used as the main drain outlet. The sprinkler contractor can run a hose from the valve outlet to a location that will not cause water damage.

A special consideration for standpipes and sprinkler systems is when PRVs are necessary for proper system operation. Standpipes with pressure-reducing hose valves are required to have larger drain risers located adjacent to the standpipe to facilitate testing of the PRVs. These drain risers are larger than standard drain risers for sprinkler drainage and have higher flows. Proper location of these drain risers and the discharge of these drains is essential to the building’s operation.

Test connections

NFPA 13 requires main drain test connections to be installed on all sprinkler systems to monitor changes in water flow. These connections must be located in an area that allows flow of the fully open test valve for the duration of the test. NFPA 13 allows test connections to also serve as the main drain connections for the sprinkler system.

Typically, a test and drain valve assembly is installed to allow for testing of the water flow without having to drain the entire system. The test and drain valve has an orifice that simulates the flow from a single sprinkler head and a sight glass that allows for visual confirmation of water flow once opened. Test and drain valves can be found at the end of the sprinkler system or at the system riser for wet pipe systems.

Ball valves are also permitted to be used as the test connection; however, they require a separate inspector’s sight glass, and the main drain valve must be fully opened to inspect the system’s water flow.

In addition to main drains, remote testing locations are required for dry and preaction sprinkler systems to test how quickly water can be delivered to the most remote location of the dry pipe system.

Auxiliary drains

When portions of a sprinkler system are isolated and cannot be drained back to the main drain, NFPA 13 requires the installation of auxiliary drains to allow drainage of trapped water. Auxiliary drains are required at locations where a change in elevation of the sprinkler system piping prevents water from flowing through the main drain valve.

Common applications where auxiliary drains are installed include dry and preaction sprinkler systems. Remote testing locations are required on dry pipe sprinkler systems to test how quickly water can be delivered to the most remote area of the system. After the discharge of a dry or preaction system, the system must be reset, and all piping must be drained and refilled with compressed air or nitrogen.

The effects of trapped water in these systems can be costly. Proper drainage is essential to eliminate standing water and condensation, which can have corrosive effects on the piping over time, leading to pinhole leaks and rendering the sprinkler system ineffective.

Auxiliary drains are used after the main drain valve is opened, allowing any excess water and condensation that could not be flushed by the main drain to leave the system. It is crucial to have auxiliary drains located at low points and other areas where the system cannot be routed back to the main drain. These drains should be accessible, particularly in areas subject to freezing, to allow quick drainage in the event of system activation.

Sizing is based on sprinkler system type and the volume of the isolated section of pipe. Wet pipe systems and preaction systems in nonfreezing conditions have different auxiliary drain size requirements than dry systems and preaction systems in freezing conditions. In all cases, a drain valve is required where an isolated section of pipe has a capacity for more than 5 gallons of water.

In wet and preaction systems in nonfreezing areas, auxiliary drains must have at least a 3/4-inch valve where the capacity of the isolated portion of pipe is between 5 and 50 gallons, and at least a 1-inch valve where the capacity is more than 50 gallons. Dry and preaction systems serving areas subject to freezing must have two 1-inch valves separated by a 2-inch by 12-inch drop nipple.

Discharge

Where possible, the main drain should run to the building exterior and discharge water away from the building. Provisions should be in place to prevent intentional or unintentional clogging and freezing of the drain. A down-turned elbow helps direct water away from the building and prevents clogging issues.

When the drain discharges to the building exterior, NFPA 13 requires a minimum of 4 feet of exposed drain pipe to be installed in a heated area between the drain valve and the exterior wall, where subject to freezing. This section of pipe creates a frost break between the exposed exterior drain piping and the upstream system piping.

In cases where running the main drain to the building exterior is unfavorable or prohibited by local standards, NFPA 13 allows the main drain to discharge to a drain connection capable of withstanding the flow of the drain.

Oftentimes the sprinkler system main drain discharges to a hub drain sized to handle the full flow of the open drainage valve, with an air gap between the two pieces of equipment. This hub drain then leads to a sump, which discharges the water elsewhere. It is critical to coordinate closely with plumbing engineers to determine how much flow needs to be accounted for by the drain connection and sump, and to ensure that the discharge location complies with local health department guidelines and water regulations.

There are several requirements for drainage discharging to a drain connection:

• Direct interconnections between sprinkler drains and sewer piping are prohibited by NFPA 13.

• Drain piping is prohibited from terminating in blind spaces under a building.

• The drain discharge point must be readily visible to ensure that no obstructions are present and no water damage occurs.

• When installed underground, drain piping must be corrosion-resistant.

Identification

All drain valves on a sprinkler system must be identified and labeled with permanent signage as required by NFPA 13. Signs should be made of weatherproof metal or rigid plastic and secured with corrosion-resistant wire, chain or other approved means.

There also must be separate means to identify whether drain valves are opened or closed. Additional signage is required at the system riser to indicate the number and location of auxiliary drains serving the sprinkler system.

Planning and designing sprinkler systems requires close coordination with plumbing engineers and architects. Designing sprinkler systems with proper drainage and identification is crucial for ensuring the longevity of the system. Taking the time to understand drain locations and sizing, and properly coordinating their discharge locations, avoids water damage and ensures that fire protection systems function effectively.

Eugene Green, PE, has been working as a fire protection engineer at SmithGroup since 2022, with five years of total experience. He has assisted in designing multiple fire suppression and fire alarm systems and conducted life safety analyses for both new construction and renovation projects. Green’s experience encompasses multiple sectors and building types, ranging from higher education labs and cultural centers to nationally recognized museums.