Jobsite visits are an essential piece of delivering a successful project. Clients, architects, contractors and project managers can all benefit immensely from having your eyes and expertise on a project as it gets built.

As a plumbing engineer, you also benefit from understanding how contractors are executing and building what you’ve designed, how they interpret your drawings and specifications, and what kind of product they are delivering to your clients. Too many buildings get built without an engineer on the design team ever setting foot in it while it’s under construction, and that carries a risk to the project and its owner.

For this reason, I regularly encourage the architects and project managers I work with to build time and cost into the construction administration phase of a project for engineering visits.

For everyone involved to get the most out of your visit to a jobsite, you need to understand what is most worth your time to look for when you’re walking the site. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to discuss a general observation visit when work within the walls and ceilings are still visible. Visits that involve corrective work, punch lists and other intents require a different approach and aren’t covered here.

Before You Arrive

Before heading to a jobsite, have a clear plan of what you intend to do and observe. Your time at a jobsite is valuable and often limited and arriving without a plan like this ends up wasting it and perhaps even missing something important. Be prepared to document everything you see and discuss through photos, meeting notes and a post-visit observation report — all these things help manage risk to you and your client and avoid change orders and claims later on.

Notify the general contractor well ahead of time of when you’ll be on site — he and his subcontractors will be better prepared to show you what you want to see and coordinate time with them.

Also, ask ahead of time for a meeting and walkthrough with the plumber so he can give you an overview of his work, answer any questions you have, and ask any of you as well. Get a general understanding of what work has been completed, what remains to be done and any challenges for either.

After meeting with the general contractor and the plumber, perform your own walkthrough without any others present. This allows you to observe what you want on your own time, giving you free rein of the site. If you discover deficiencies or irregularities, it also allows you freedom to look more closely at other areas that may have the same issues.

The Top Five

While not an exhaustive list, the following five items are the ones I’ve found to be the most valuable and important things to look at while you’re on a jobsite.

1. Conformance to your specifications and submittals. One of the first things that many engineers rightly do is ensure that the installed equipment and materials are what was specified and submitted. Project budgets and profit margins are getting tighter all the time, and construction bidding is accordingly getting more competitive.

An unfortunate result of this is contractors looking for more opportunities to cut construction costs, sometimes at the expense of a quality design. Tight specifications are your first line of defense against this, and the submittal process is your second.

Builders are contractually obligated to install what was specified and submitted. As such, most of them will not risk deviating from this after the fact, but I have occasionally seen otherwise. One contractor went so far as to have rough plumbing installed without producing a single material submittal. Accordingly, it is your responsibility to confirm that contractors are installing what was agreed upon.

Getting photos of materials and equipment and checking them against specifications and submittals is one of the best ways to ensure conformance. It is often easy to confirm this with major equipment, as the manufacturer and model are on the unit.

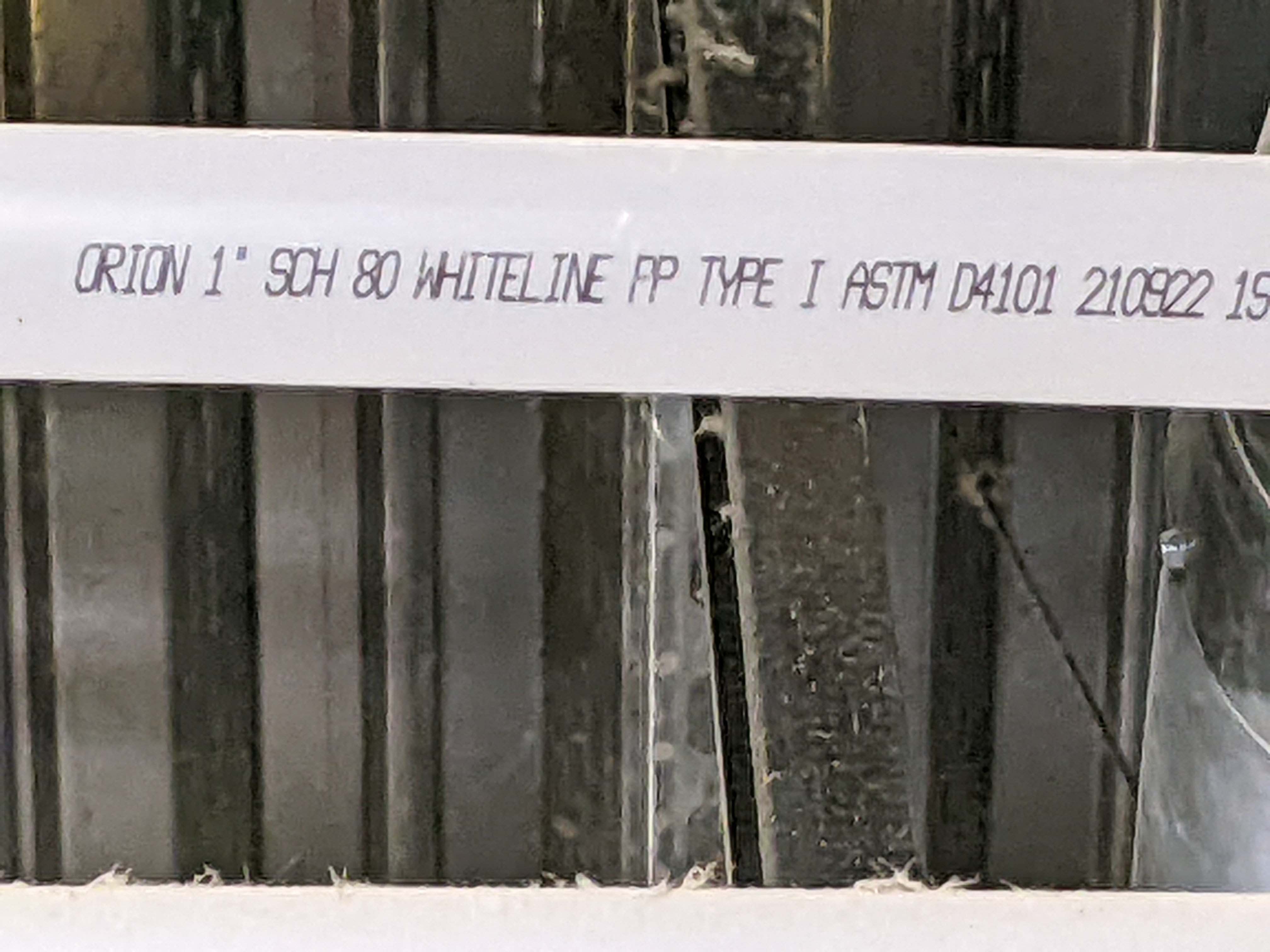

For pipe and pipe accessories such as valves and flow controls, look for stamps on the material showing the standards they were manufactured to and tags showing the manufacturer (see Figure 1). If you have access to the plumber’s material staging area, get a close look at the materials present there and also any packaging. It will often identify the manufacturer and model number.

|

|

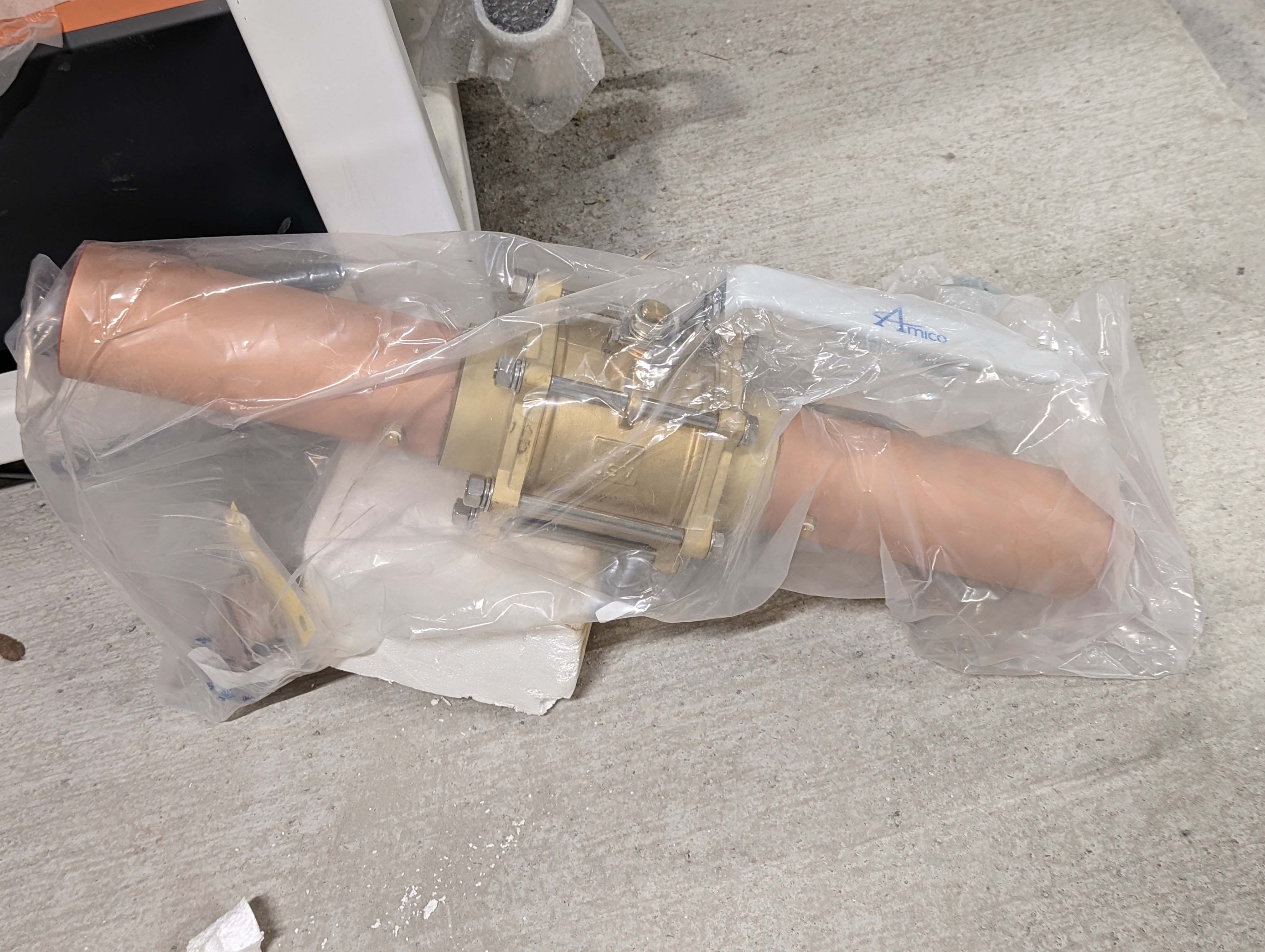

An often-overlooked item in this area is pipe and equipment support (see Figure 2). Make sure that pipe is hung and supported per the methods you specified and per code requirements. If the project is in a seismic area, this task is even more complicated, as you will have to look at associated pipe and equipment bracing.

2. Use of approved construction methods. Confirming acceptable construction methods can be done in similar ways as conformance to specifications and submittals. Once again, this is a broad area that some contractors exploit to meet construction budgets. Your specifications should clearly describe the approved construction methods, such as pipe joining, equipment and fixture connections, floor and wall penetrations, system identification, and others.

You can usually determine the pipe-joining methods contractors are using by observing what is installed and what materials are present in their material staging area. Looking at the tools they use is also helpful. For example, you would not expect to see flux, solder and torches for work that was only approved for pressed joints and fittings.

When medical gas work is being done, be sure that they are brazing joints rather than soldering. One way to tell this is if you see a nitrogen rig present, as brazing should be done with a continuous dry nitrogen purge. You can often tell by the coloring of finished pipe joints; brazed joints will show black crusts (copper oxide) at the joint and often show a color spectrum farther out, whereas soldered joints will have neither of these things (see Figure 3).

In addition, ensure that connections from system pipe to equipment are consistent. For example, you would expect a connection on a threaded shower valve to be made with a threaded pipe and union, but I have seen instances where plumbers do not spend this effort and solder the connection instead. Similarly, you would expect connections to energized vibrating equipment such as pumps to be made with flexible connections instead of hard pipe.

Noting general workmanship is a related item. Make sure that pipe is level, straight, sloped appropriately, supported properly, does not have excessive solder and is undamaged. Open pipe ends should be capped or plugged if they are not receiving a connection within a few hours, and medical gas valves and accessories should be bagged until installation.

System identification is another area that engineers often overlook. Follow pipe through corridors and into the rooms they serve and ensure they are labeled correctly, labeled as often as specified (especially before and after a wall penetration), and that flow arrows are shown in the correct direction.

Many engineers also specify valve tags with unique numbers on each and corresponding charts identifying them for their owners after occupancy. Checking that these tags are present and labeled correctly is much easier to correct when rough plumbing is still going in.

3. Design scope. It may seem obvious, but making sure that the contractor is installing the full scope of your drawings also is critical. The easiest place to understand a contractor’s scope of services is in a pre-bid meeting where you can ask questions about what they intend to cover, but engineers are not often invited to these. If this is the case, you should ask the general contractor who is covering what scope of work before walking the jobsite.

A plumbing company may not necessarily install every aspect of your drawings and may instead subcontract some of the work to others. For example, some plumbers are not skilled in brazing or welding and, as such, may subcontract medical and fuel gas work out to HVAC pipefitters instead.

If this work is not present during your visit, do not assume that it is forthcoming; ask the general contractor what was agreed to and who is installing what. They will often tell you that this work is covered by another contractor, but I have occasionally seen it missed completely.

4. General routing. You should ensure that the contractor generally followed the pipe routing on your drawings, as this is often an indicator of how closely they followed the rest of your design. Some minor routing deviation is normal and to be expected, but these should be minimal, especially if there was a subsequent building information model coordination effort.

Major reroutes, however, may seriously deviate from the contract documents and have an unintended effect on your design intent. For example, you may have shown water mains being routed in corridors with valved fixture branches going to the rooms they serve with the intent of maintenance personnel being able to isolate these rooms from the outside. Instead, if the contractor ran the mains through the rooms, this may not be acceptable to your client.

In cases like these, you should always document the built condition, include it in your observation report, describe the effect it has on your design, and get your client’s opinion after they review your report.

5. System testing. Confirming that the contractors have performed the code- and specification-required system tests is a critical piece of ensuring they will function safely, properly and without failure once put into service. Your specifications should require the contractor to send you copies of these test reports, but asking about their status and testing regimens while on-site is also helpful in ensuring they are completed.

Before arriving at the site, know what system tests are required by code and your specifications and be prepared to discuss them. Potable water system disinfection is almost always a given — many plumbing codes require that potable water systems be flushed and chlorinated prior to being put into service.

For domestic hot water systems, you should expect to see a balancing report that includes the achieved flows at each balancing valve and temperatures generated by the water heaters, the building mixing valve and the hot water return line. NFPA 99 requires medical gas systems to undergo multiple tests by an ASSE 6030-credentialed professional as part of the verification process; you should expect to see copies of the test results along with any required corrective actions.

Hydrostatic or pneumatic leak-testing of water and drainage systems is not always required by code, but often a good idea to specify. If you have a water purification system for a laboratory or hospital, you will want to get reports of the final generated water quality and ensure it meets what you have specified.

Observation Reports and Closeout

After you have conducted your site visit, prepare a report of your observations. Include dates and times of your visit, general observations of the jobsite (construction progress, cleanliness, systems and equipment present, etc.), names of field personnel you met with, and observations of both correct installations and deficiencies.

For deficiencies, include requirements for corrective action if they are a clear violation of code, contract documents or submittals, and suggestions if they are not. Include all the photos you took during your visit, and match the ones showing your observations to the corresponding deficiency.

Once complete, send your observation report to the architect and engineer of record, general contractor and client or the client’s representative. Expect that you may get comments back from all these, especially if you observed deficiencies. Be prepared to explain your observations further and defend the recommendations you’ve made.

While often time-consuming, jobsite visits are an essential part of delivering a quality project that meets your client’s goals. They can be valuable learning experiences for both engineers and contractors; after 15 years in the industry, I still learn new things every time I visit a site.

Most clients will appreciate you spending your time ensuring they are getting a quality product. It will often strengthen your relationship with them, make you a better engineer — and help you win additional work.

Aaron Bock, P.E., is a senior plumbing engineer at ERDMAN and has been designing plumbing systems for the health-care industry for 15 years.