When is the best time to perform a combustion analysis for the boiler: fall, winter or spring? This debate has been argued for as long as I have been working on boilers.

Fall

“Tune it before the heating season so it’s perfect on day one.”

Downside: The building overheats in minutes, and now you’re stuck waiting hours for the loop to cool before adjusting.

Winter

“Test it under a real load when the boiler is working hard.”

Downside: By then, half the heating season has passed with who knows what air-to-fuel ratio.

Spring

“Get it ready for next year.”

Downside: Same overheating issue as Fall, plus five long months for something to get bumped, rusted, clogged or stepped on.

Each one sounds reasonable. So, when is the best time to test the boiler? Every single time you open the boiler room door — and no, that’s not overkill.

Here’s why:

Safety: Things happen in boiler rooms when you’re not there. I’ve seen burner linkages bent from clumsy insulators standing on the burner, combustion air openings blocked with wood and spiders building homes inside the gas piping. Verifying combustion on every call guarantees the boiler is safe that day — not six months ago.

Liability: Documented combustion readings are priceless: “Your Honor, here are the numbers from March 14, all within the manufacturer’s specifications.” Hard to argue with that.

Professionalism: While Low-Bid Pete is in and out in 20 minutes, you’re the tech who proves the equipment is running efficiently and safely. Owners notice that.

I spoke with Tyler Nelson with Sauermann Group, a manufacturer of combustion testing equipment, and asked what the top mistakes techs make when doing combustion testing:

Not auto-zeroing the analyzer outside in fresh air with probes disconnected: If you zero-out the analyzer in a room filled with flue gases, your readings are going to be way off, and you could be breathing in toxic fumes.

Using as-measured carbon monoxide readings instead of carbon monoxide air-free gives a false reading of the boiler emissions: More on this below.

Not understanding what each reading means or which adjustment affects it: Adjusting for one part affects another.

Only pulling the analyzer out once a year (or never): A boiler’s combustion changes constantly. Annual testing isn’t enough.

I’ll add the one I see often:

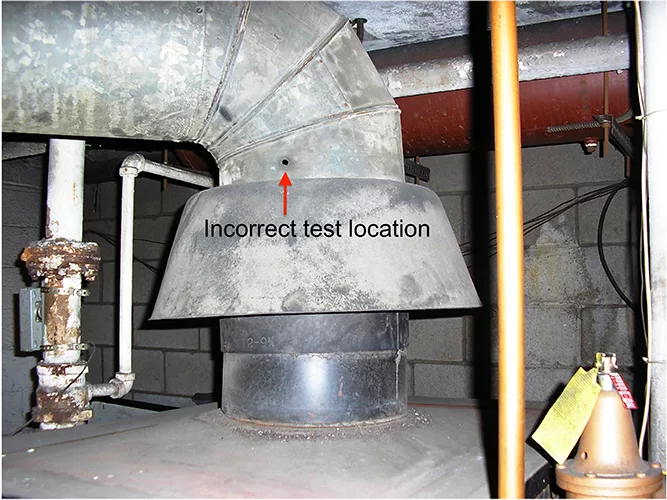

Testing in the wrong spot: Some techs insert the probe into the flue pipe after the draft diverter or barometric damper. Those devices deliberately dump room air into the flue, diluting everything. You’ll get beautiful-looking numbers while the boiler soots up like a coal stove. Always test before where the dilution air enters, usually right above the boiler flue outlet or in the stack before the diverter or barometric damper.

Two tests

Before you even look at oxygen, carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide, check these two pressures: incoming gas pressure and boiler draft. When the boiler was designed, the manufacturer used a specific furnace or combustion chamber pressure. The combustion chamber is where the air and fuel are mixed and ignited.

Rather than having the technician try measuring pressure in that explosive combustion chamber, they suggest measuring the incoming gas and the draft pressure. One is the boiler input; the other is the boiler output.

Think of it like a seesaw: If the combustion chamber pressure is too low, the heat doesn’t get released into the water and instead goes up the stack, wasting fuel. If the combustion pressure is too high, you could have flame impingement, damaging the boiler’s metal surfaces.

A manometer or pressure gauge is used to check the pressure going into the burner. Typical settings are:

• Atmospheric burners: about 3.5 inches water column (WC) (natural gas)

• Power burners: 7 to 14 inches WC

The next test is the boiler draft pressure, measured in inches of WC. For Category 1 appliances, the draft is slightly negative, ranging from -0.02 to 0.05 inch WC. If the draft is excessive, it pulls the flue gases through the boiler too quickly, reducing efficiency. This is indicated by elevated flue gas temperatures. If the draft is too low, the heat does damage to the burner head and metal surfaces.

Let’s look at the other readings we get with a combustion analyzer:

• O₂ (oxygen), read in percent, is the leftover oxygen in the flue gases after combustion; it’s typically 3% to 6%. The air you breathe contains about 21% oxygen. If the reading is too high, it lowers efficiency. If it’s too low, you could have elevated carbon monoxide.

• CO₂ (carbon dioxide), read in percent, is the byproduct of combustion and is typically 10% to 12% for gas. O₂ and CO₂ move in opposite of each other: When O₂ goes up, CO₂ goes down and vice versa.

• CO (carbon monoxide), read in ppm (parts per million), is a byproduct of combustion and a dangerous one. It should be as low as possible, typically less than 100 ppm (as measured) for most equipment. The best way to evaluate the CO levels in the flue gas is by using carbon monoxide air-free.

• COAF (carbon monoxide air-free) is read in ppm (parts per million). In the past, when you discovered elevated CO readings in the flue gases, you had two choices. You added more air to the flame to dilute the readings, or you found and repaired the problem. The lazy techs just added more air. The industry caught this ruse and developed a calculation called CO Air-Free. COAF removes the excess air from the calculation to get a truer reading.

Let’s say your gas tank is dripping one drop of gasoline per second.

Rather than repair the leak, you spray water on the driveway. It doesn’t repair the leak; it simply dilutes it and masks the problem. If a system has a lot of excess air, the measured CO might appear low, but the actual CO being produced at the flame could be dangerously high. CO air-free measurements correct that.

• Stack temperature, or flue temperature, is the net stack temperature (flue temp minus room temp). It should be around 300 F to 450 F for a noncondensing boiler and 100 F to 140 F for a condensing boiler. If the stack temperature is too high, it means the boiler isn’t transferring heat into the water.

• Excess air, read in percent, is the extra air beyond what’s needed for perfect combustion, usually 30% to 50%. The rule of thumb is that it takes 10 parts of air for every part of gas for perfect efficiency. This varies with the combustion air temperature and humidity.

• Efficiency, read in percent. The analyzer calculates this from O₂ and stack temperature. The 80% furnace should read 78% to 83%. The 90%+ furnace should read 90% to 97% if it’s condensing properly.

There is no best season to test a boiler. I prefer to check the combustion levels on each service call. Do it right, document it and sleep better at night, and leave Low-Bid Pete in the dust. l

Ray Wohlfarth is president of Fire & Ice Heating & Cooling in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the author of 14 technical books on boilers and hydronic systems, plus a children’s book. He is the creator of the popular YouTube channel Boiler Room Detective, where he shares troubleshooting tips and lessons from real boiler rooms. With decades of hands-on experience, Wohlfarth combines technical expertise with storytelling to make complex heating topics practical and approachable.