Fire sprinkler protection in areas used for storage is a daunting task for two main reasons: the fire risk inherent to stored commodities and the difficulty of determining the appropriate protection methods. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) provides a veritable tome of information on protecting indoor storage areas in NFPA 13 (2025), Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems.

However, there is so much information covering more permutations of commodities, storage configurations and building geometry that it can feel like a gargantuan task to decipher the code and determine what is appropriate for any given storage area. By breaking the process down into easier, smaller processes, though, one can confidently and accurately come to a design for their storage area.

In Part 1 of this column, from this magazine’s January 2025 edition (https://bit.ly/3LP53UC), we covered the topics of commodity classification, storage height and protection of low-piled and miscellaneous storage. In this column, we will continue by summarizing the protection of high-piled storage.

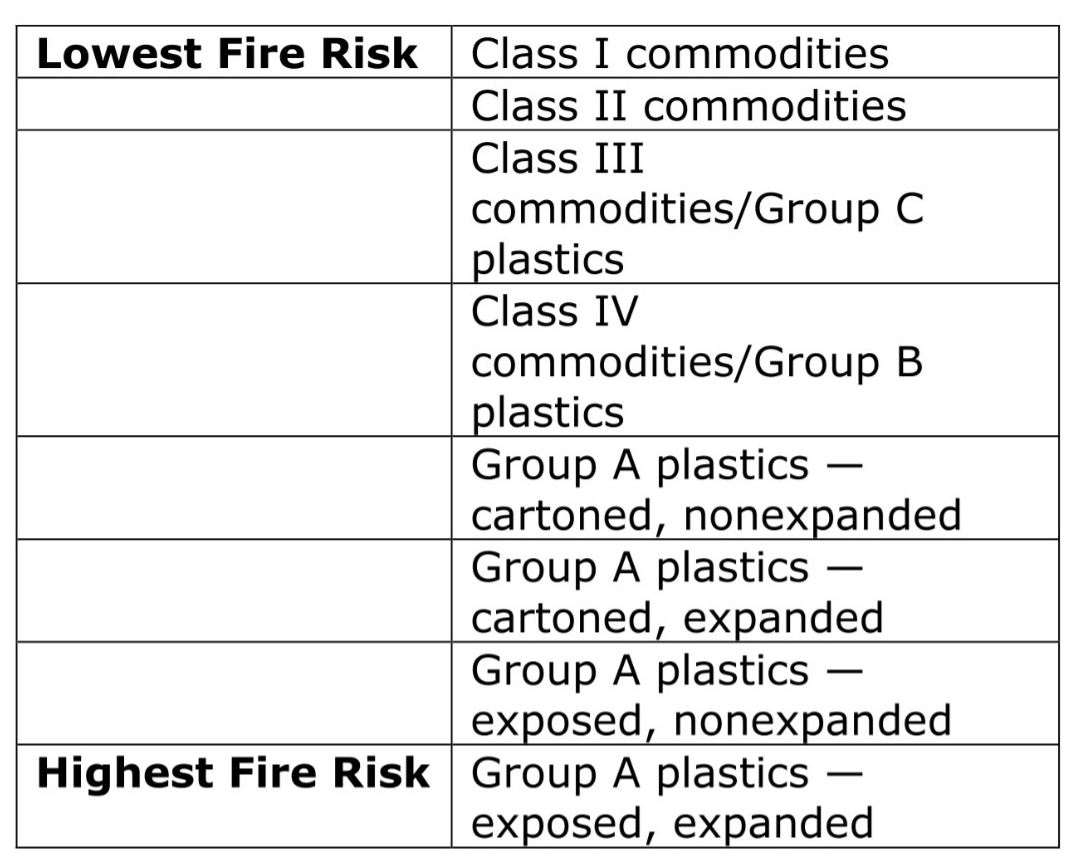

To recap, the first step is always analyzing what is being stored. In this process, one can use definitions and tables in NFPA 13 to determine the classification of their plastic and nonplastic commodities. It is important to remember that analyzing the commodity being stored is as important as examining what the commodity is being stored in and on.

For example, empty glass jars might present a minimal fire risk, but if they are stored in solid wooden boxes on a reinforced plastic pallet, then the wood and plastic present a considerable fire risk. The following table ranks the classification of commodities from lowest to highest fire risk:

The next step is to determine the configuration of the stored materials. NFPA 13, Chapter 3, sets definitions for the following storage orientations: solid-piled, bin-box, palletized, shelf, single-row rack, double-row rack, multiple-row rack and back-to-back shelf storage. The definitions may seem similar, but the slight differences between them can lead to entirely different dynamics in a growing fire.

For example, multiple-row racks will create a higher volume of shielded combustibles than single-row racks, and palletized storage may allow for easier oxygen passage through the stored material than solid-piled storage, which can contribute to faster and more dangerous fire growth. We also need to consider the aisle width in some storage configurations, as narrower aisles lead to a denser collection of stored commodities and, therefore, a higher risk.

Types of fire sprinklers

The material being stored (i.e., its commodity classification) and its storage configuration are often provided to designers by clients, building owners or architects. While designers may have a small say in how these materials may be stored, we often find ourselves in a reactive role, needing to protect that commodity and configuration work in any way we can. As such, the first choice we need to make as designers is the type of sprinkler we will choose to use.

For high-piled storage protection, we can choose from ESFR (early suppression, fast response), CMSA (control mode specific application) and CMDA (control mode density/area) sprinklers. The main differentiators between these types of sprinklers are their hydraulic calculation and fire control methods.

CMDA and CMSA sprinklers are designed and tested to control a fire and limit its spread, rather than to extinguish it. They are characterized by relatively high flow rates at relatively low pressures. Much like designing for nonstorage occupancies, the hydraulic calculations for CMDA and CMSA sprinklers are based on a hydraulic design area and a certain density of water flow discharging from the sprinkler (measured in gpm/ft2).

ESFR sprinklers, on the contrary, are designed to extinguish a fire. This is accomplished by high water discharge, high pressure at the sprinkler and large water droplets that can penetrate the flame without instantly vaporizing and attack and extinguish the seat of the flame. Unlike CMDA and CMSA sprinklers, hydraulic calculations are typically performed by specifying a minimum pressure available at a sprinkler head (generally based on the manufacturer’s specification) at several sprinkler heads that are dictated by NFPA 13 or other standards.

There may not be one correct answer for which sprinkler type to use, depending on the commodity and configuration being stored. ESFR sprinklers are the industry-preferred sprinkler type because of their ability to extinguish a fire rather than only control it. However, there may be cases where very small, isolated storage areas or high-piled storage of Class I commodities would be better served by CMDA or CMSA sprinklers. It is up to the designer to review the relevant chapters of NFPA 13, assess the feasible design criteria and make the final decision.

Protection of high-piled storage occupancies

Let’s now chat about those relevant chapters in NFPA 13. In the 2025 edition, Chapters 21 through 23 provide information on the protection of high-piled storage occupancies with CMDA, CMSA and ESFR sprinklers, respectively. Each chapter includes subsections detailing sprinkler requirements based on commodity classification and configuration.

For example, Chapter 21 has one subsection covering nonrack storage of Class I through IV commodities and another subsection covering rack storage of Class I through IV commodities (among other subsections). Chapter 23, however, has one section covering both rack and nonrack storage of Class I through IV commodities.

It is important, especially in Chapters 21 and 22, to read the first clause in any subsection to examine the scope the subsection covers. If you find that the subsection does not cover the scenario you are trying to protect, I recommend moving on to Chapter 23, which covers a wider range of storage scenarios.

The last significant aspect to consider is the use of in-rack sprinklers. Many tables throughout Chapters 21-23 point to Chapter 25, which is on the protection of rack storage using in-rack sprinklers. The point of in-rack sprinklers is simple: the presence of storage within racks can create high quantities of shielded combustibles.

If we rely solely on ceiling-level sprinklers, a fire could grow deep within the rack storage to the point where the sprinkler system would be overwhelmed and unable to control or extinguish it. These sprinklers are fitted with a wire cage guard to avoid damage from those loading/unloading the racks, and often with a water shield above to prevent any ceiling-level sprinklers from discharging water onto the sprinkler’s thermal element and preventing activation of the sprinkler.

Sprinkler design examples

Now that all the required information has been touched upon, let us consider a few examples that help illustrate a basic process for determining sprinkler design for storage occupancies.

For our first example, a client tells us they want to store a Class IV nonencapsulated commodity in solid-piled storage at a height of 18 feet, with a ceiling height of 28 feet. We will look at both CMDA and ESFR sprinklers and determine the best option from there.

For CMDA sprinklers, this takes us to Chapter 21, and specifically to Chapter 21.2 and to Table 21.2.2.1.1 (Figure 1). This table is relatively easy to use: our required density will be 0.3 or 0.39 gpm/ft2, depending on the sprinkler’s temperature rating we specify.

For the discharge characteristics of the sprinkler, we can look at Sections 21.1.3 and 21.1.4. They state that if our required density is between 0.2 and 0.34 gpm/ft2, then a standard-response sprinkler with a minimum K-factor of 8.0 is required. If our density is greater than 0.34 gpm/ft2, then a standard-response sprinkler with a minimum K-factor of 11.2 is required.

For ESFR sprinklers in this example, we will venture to Section 23.3 and Table 23.3.1 (Figure 2).

This table is also relatively simple to use, but we do have to be careful in our example. Although we only have a storage height of 18 feet, our ceiling height exceeds 25 feet, so we cannot use the first line in the table. The second line of the table will have to do. This exercise has left us with both a CMDA and an ESFR option — either one will suffice.

For our second example, let us consider the storage of cartoned Group A plastics at a height of 30 feet, with a ceiling height of 35 feet and 4-foot aisles between single-row open racks. For CMDA sprinklers, Section 21.6 immediately points us to Chapter 25, indicating we will use in-rack sprinklers.

Section 25.4, which covers in-rack sprinklers with CMDA ceiling sprinklers, gives us separate hydraulic criteria for our in-racks. Table 25.4.1.1 shows that, given our storage criteria, we will have eight sprinklers, each flowing a minimum of 30 gpm if we have one level of in-racks, or 14 sprinklers, each flowing 30 gpm if we have more than one level of in-racks.

For our ceiling-level sprinkler design criteria, we are directed to Section 25.4.3.3.2 and then to Figures 25.4.3.3.1.1(a) through 25.4.3.3.1.1(g). By selecting the criteria from the figure that correspond to the space you are protecting, you will get the appropriate design criteria for the ceiling-level CMDA sprinklers.

Unfortunately, a comprehensive article on high-piled storage design would be almost as long as the NFPA chapters on high-piled storage itself. However, what I hope you can take away from this column is this: it is easy to get lost in these NFPA chapters without a plan of action. However, if you determine your commodity type, obtain storage configuration details and follow the trail of crumbs left by Chapters 21, 22, 23 and 25 in NFPA 13, then the answer is there waiting for you.

The chapters and subsections are named with clear allusions to the information they contain. As long as you stay on the path that your commodity and configuration dictate, then you will end up in the right spot with a confident answer to supply to your client.

Jack DeVine, PE, is a senior fire engineer at Arup, based in Boston. He has an extensive background in designing fire sprinkler systems for various types of commercial buildings, as well as a broad foundation in fire and life safety code consulting and performance-based design. DeVine has a master’s degree in fire protection engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where he has since guest-lectured in human behavior in fire, fire modeling and evacuation modeling.