Note to self: Stop hyping green buildings. Usually, I’m suggesting to readers that they need to change. Now it seems I have to change. The good news is that I’m now preaching to the converted. After more than a decade of writing about decarbonized construction, I no longer feel as if I’m in a big empty room with just my own voice bouncing off the walls. The construction industry, particularly in the northeastern United States, is going all-in on energy-efficient, low-carbon buildings.

The bad news is that I can’t get people on the phone. The top experts in electrified buildings are working 18 hours a day. “It seems like every week we get a serious inquiry about a new project,” says architect Richard Pedranti of RPA in Milford, Pa., who specializes in low-carbon homes. “It’s been quite a year.”

As I write this in July 2021, we hear the same story from virtually all the engineers, architects and builders who established themselves early in what for so long was a niche part of the industry. Due to changing regulations, developer and realty industry attitudes, and climate conditions, that niche is now the mainstream.

Affordable, Low-Energy Homes

I first met Richard on a jobsite in the woods outside Scranton, Pa., in early January 2020. The pandemic had begun, but at that time, it was just one of many stories on the nightly news, happening mostly in China. Neither of us realized that soon most of humanity would be trapped at home for more than a year, thinking about the world we created outside and the air we were breathing inside.

Richard was proudly explaining the architectural details and modern HVAC system of a 2,000-square-foot passive house that his team was building for just $165/square foot. “We have proven it’s a myth that well-built homes are expensive,” he says. His company repeated the achievement in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Michigan and Wyoming.

The cost per square foot is different in each location, but the general picture is the same — a passive house can cost the same as a conventional house if that’s a priority. “Usually, if a passive house is expensive, they’ve used some unusual details or added some nice-to-haves,” Pedranti explains.

The Scranton building’s conditioning loads are so small that heating, cooling, HEPA filtration, energy recovery and humidity control are all managed using one small heat pump device called a Minotair Pentacare V-12. It can operate in heat pump mode, recirculation mode, intermittent mode (10, 20, 30 or 40 minutes/hour) or smart mode.

In smart mode, it prioritizes humidity management and air exchange mode, then switches to heat pump mode during calls for heat or cooling. Ventilating capacity is 20 to 180 cfm of fresh air in air exchanger mode at up to 1.6 in H2O (35 to 305 m3h at up to 400 Pa), and 80 to 250 cfm of filtered air in recirculation mode at up to 1.6 in H2O (135 to 425 m3h at up to 400 Pa).

In early 2020, Pedranti suggested that they were moving toward one replicable model for a single-family low-carbon house, but when I called him in 2021, his team was managing dozens of projects, and he admitted there were three or four or five approaches. His group was now working with two pre-fab companies that supplied factory-made, properly sealed, high-integrity wall sections, in some cases with certified windows and doors already installed in them.

Richard Pedranti in Scranton with the Minotair Pentacare V-12. It manages the home’s heating, cooling, HEPA filtration, energy recovery and humidity control. Photo: BF Nagy

Anyone who has worked for very long in construction knows there is more than a grain of truth to the saying that every job is a custom job because there are so many variables with buildings. It’s hard to create a cookie-cutter approach.

This is not comforting to hear for the many politicians and civil servants now trying to create policies for a dramatic architectural ramp up away from fossil fuels, involving government funding programs, partnerships, training regimes and inspection overhauls.

We’ve left it too long; the greenhouse gas reduction targets and timelines are brutal. It’s going to be messy. Note to self: Stop preaching and focus on best practices.

In addition to the complexity of the challenge, there are, of course, the politics — the politics of governments, and the politics of old, successful private sector boomers who are having trouble recognizing the need for change.

What this all adds up to is compromise, in the same way hybrid electric cars and hydrogen experiments are simply political waystations on the journey toward the inevitable end game — nothing but fully electric vehicles everywhere on earth.

Near-Net-Zero Office Complex

Environmentalists like me are impatient people. We want change now, and we want everything that’s possible to be fully implemented. But that’s not the way the world works. The first page of the case study for the Aurora, Colo.-based Oxford Vista Campus says, “Achieved near-net-zero electric.” Sounds unconvincing, but it turns out to be an impressive retrofit project.

It has solar panels on the roof and carport, and a geothermal heating and cooling system. It has a dedicated outdoor air system and sophisticated zone control, LED lighting and new windows. But it also has new high-efficiency gas boilers because the geothermal handles 70 percent of the load, rather than 100 percent.

Undoubtedly there were site limitations that prevented them from going all the way to clean renewables. Someday they likely will.

EnergyLink, the company that completed the project, is a great contractor, undertaking many modern retrofits. Crazy busy these days. It just received an assignment to install solar on the roofs of 46 municipal buildings in Asheville, N.C. The company’s phones have been buzzing since it became accredited by The National Association of Energy Service Companies, which puts it on lists that are reviewed by local and state governments, as well as the federal

government.

Down in the weeds of technological disruption, everyone is in a different place on the timeline. For example, if you want to see where the southern United States might end up in terms of rooftop solar and home batteries for storing electricity, you would probably look at where California already is now.

If you want to see where the northeast, Canada and the north-central United States will end up with building envelopes and clean heating, you would probably look at where New York is trying to get right now. The state is attacking the problem on numerous fronts that sometimes seem disjointed. It’s progress. It’s change. It’s messy. But it’s happening.

In the United Kingdom, the government started off with a home efficiency program and a heat pump switch-out program. Then for whatever reason, likely cost, they withdrew the efficiency but kept the heat pump program in place. This is likely to lead to numerous comfort complaints in the future. Change is messy.

Multi-Pronged Clean Tech Blitz

In the past few years, we’ve reported on The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) pouring millions into geothermal financing and incentives, first with a few operators, then with major player Dandelion, then an organized group of medium-sized installers, and finally on community beta projects with utilities.

We’ve reported on New York City getting tough legislatively for new construction and existing buildings. It’s developed passive house programs with Handel Architects, Steven Winter & Associates and others for new builds, and with Chris Benedict’s firm for retrofits to large existing multifamily buildings with tenants in place during the upgrades.

The early successes led to the state realizing that the clean energy transition is huge and multi-faceted, and so is the opportunity to establish New York and the northeast as a vibrant hub, exporting cleantech expert services and new construction products to transitioning cities all over the globe.

The latest chapter in the state’s support story involves funding and assisting start-up manufacturers. ScaleForClimateTech and VentrureForClimateTech are two names for essentially the same program providing companies with tools, training, talent and the nondilutive funding necessary to begin building a company around their climate solutions.

HVAC Sensors for Efficiency and Predictive Maintenance

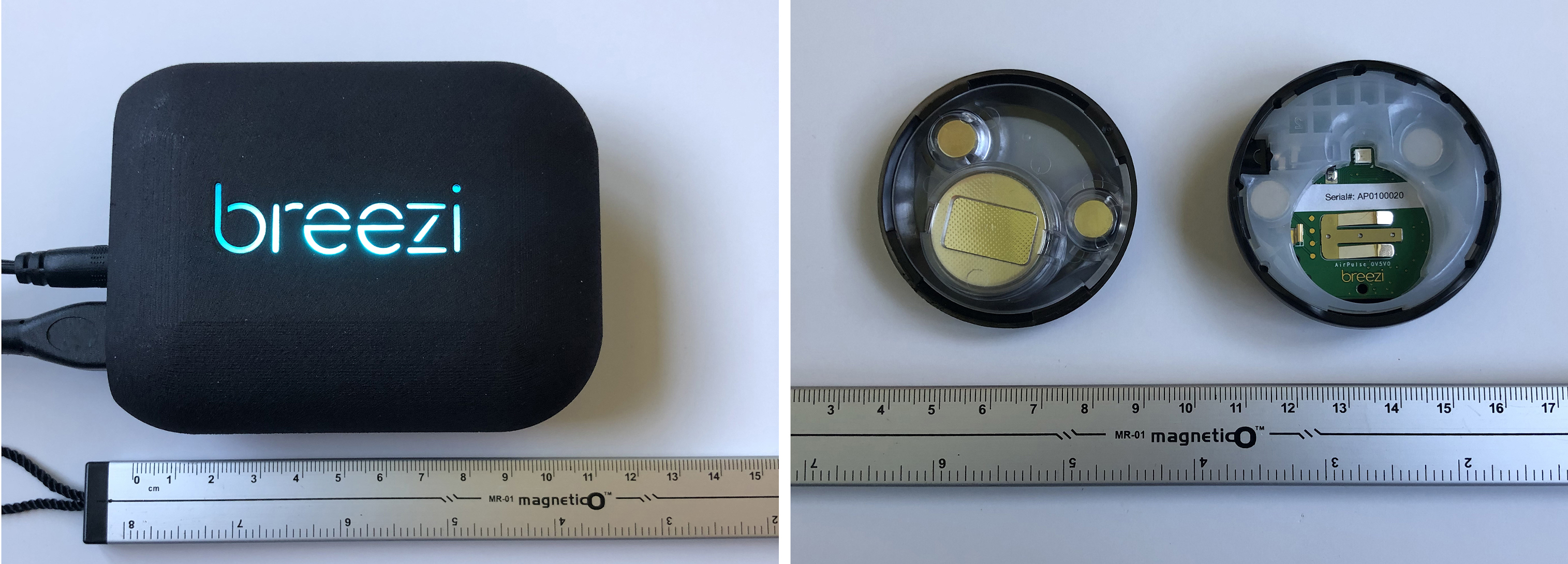

“The NYSERDA program has been incredibly helpful,” says Tim Seaton, co-founder and CEO of Breezi.io, which is establishing a manufacturing plant in upstate New York to make sensor products that may accelerate the energy efficiency of common heating and cooling equipment, and comprehensively address predictive maintenance.

This latter goal received a lot of attention but still seems stalled in terms of concrete progress. Breezi developed affordable and easy-to-install wireless products based partly on some of what Seaton learned in a past life when he worked on predictive maintenance studies for industrial-scale heavy equipment for Shinkawa in Japan.

Breezi sensors and monitoring equipment for predictive maintenance and energy efficiency are small and wireless.Photo: Breezi.io Inc.

VentrureForClimateTech is trying to accelerate the start-up process. “They have an amazing team that has been tremendously helpful with defraying costs as we move production to New York from North Carolina,” Seaton explains. “They provide a deep analysis of our manufacturing readiness, help us improve quality management, sourcing and introduce us to potential partners and customers.”

He adds that the start-up received similar support from LaunchNY, a nonprofit backed by major foundations, corporations, federal and state entities. “They have provided mentoring, advice and introductions in just our first few months working together. Another great resource!” Seaton says.

Dynamic Air Cooling is a Polish company also receiving government help to establish production in New York for cooling equipment using no synthetics — just sophisticated technology and air as a refrigerant. I will be doing an expanded profile on this company in a future column.

BEAD is a third example. It’s a California software company that sees the northeast as a logical place to establish a presence. BEAD creates digital models of buildings and analyzes real-time data to understand occupancy patterns, saving commercial real estate investors from $50,000 to

$1 million annually without retrofits.

It’s easy to see all around us that climate change is now a compelling threat. Governments and corporations are acting aggressively to address it, and it represents a tremendous economic opportunity for regions that can figure out how to capitalize on the ramp-up. Note to self: Hang on tight. It’s going to be a wild ride.