If you do a quick search of the phrase “required reading,” you’re likely to see the names of classic books such as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Of Mice and Men,” “Catcher in the Rye” and “Fahrenheit 451.” The latter is a novel of a dystopian future where books are banned and burned. Can you imagine that? A world without reading?

I can’t. I’ve read most of what Elmore Leonard has written and everything Dennis Lehane has penned, but it’s technical reading that gets most of my time. I like being entertained, but I love learning new things. The most basic things we should be reading are installation instructions — because far too many of us aren’t.

I’m a member of four or five heating and boiler groups on social media, and I contribute when and where I think I can help or give somebody their due props. If there’s a way to help someone get to the next step, I’m ready and willing to help. I don’t want to be the guy who rips another’s work as he sits atop his high throne. That ain’t cool; the only thing it does is make you look like an immature fool. Most times, I sit back and admire the fine craftsmanship that guys and gals are churning out.

That said, there are yet other instances where I’m left scratching my head in complete bewilderment. An instruction manual comes along with every steam boiler, modulating-condensing boiler, cast-iron boiler, water-lubricated circulator, fill valve, expansion tank and mixing valve. They are included for our benefit, the manufacturer’s benefit and, ultimately, your customer’s benefit.

If you think you don’t have time to read the manual, what makes you think you’ll have time to go back and install it correctly? The key is slowing yourself down enough to realize that everybody wins when you do your homework on the front end, rather than the back end — where it’s a loss for everyone.

Common mistakes

Let’s start with a common mistake, and I know it’s common because I see it daily — the orientation of a wet rotor circulator. I don’t care if it’s a Wilo, Armstrong, Taco, Grundfos or Bell and Gossett. If you don’t get this simple thing right, your customer’s circulator will fail prematurely.

The motor must be on a horizontal plane for proper lubrication (see Figures 1 and 2). And if this egregious oversight happens to be pointed out by a competitor, you just lost a customer. All that work that went into selling that job and adding another name to your customer list is lost because you didn’t look at the installation instructions.

|

|

And with the pump manuals, no reading is involved if you want to avoid it; there are pictures! Pictures showing the right way and then other pictures with a big X through it showing the wrong way. It’s that simple. Open it up, see what’s inside, and better your game. Lose the Xs, keep the customer.

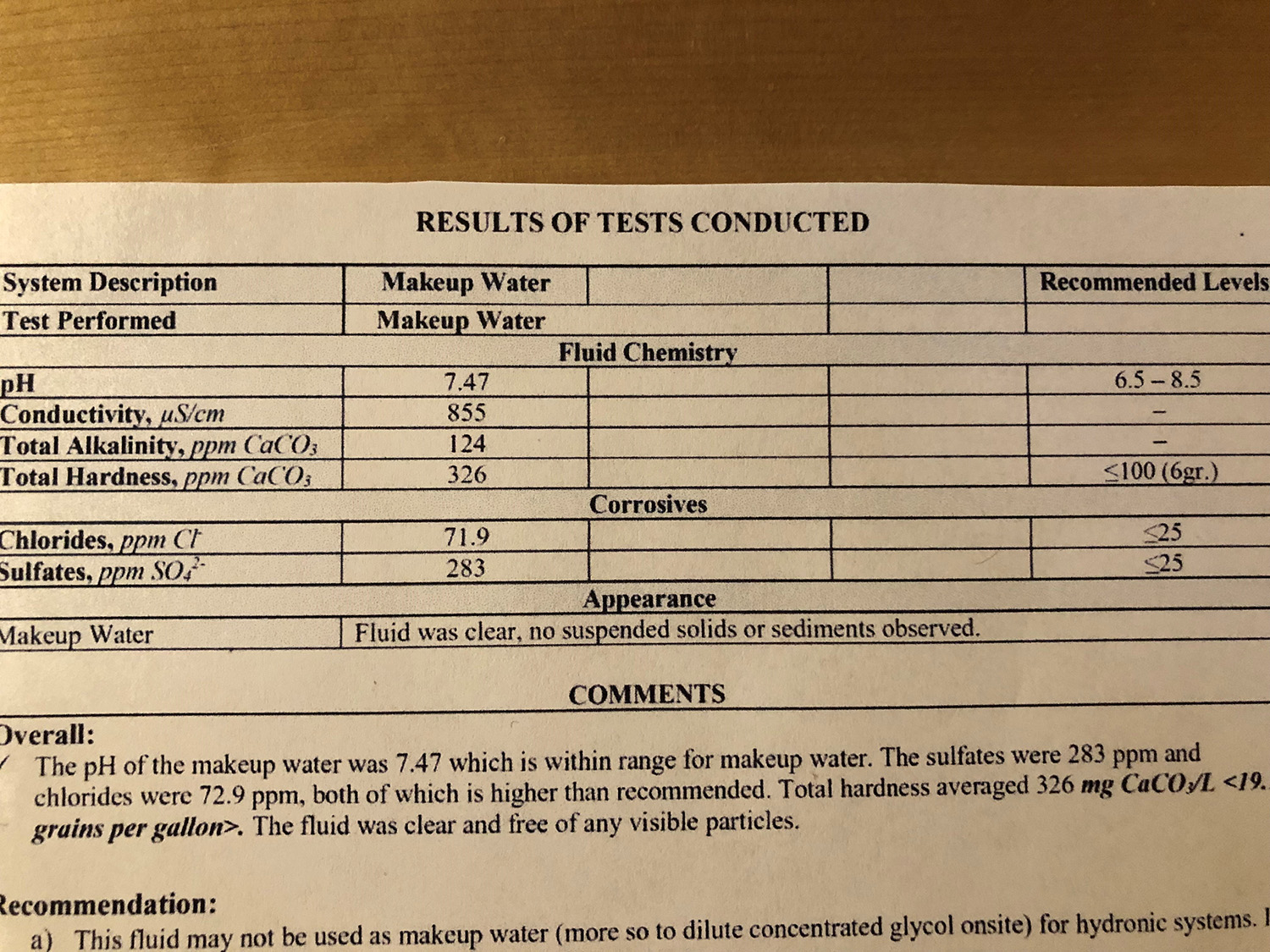

Here’s another area that’s often overlooked or not taken seriously (I’d say a little bit of both): water quality in modulating condensing boilers. I’ve paid close attention to this in recent months. As some of you know, I live in Las Vegas now; the water quality here is terrible. I knew it was bad, but the only way to know for sure was to have it tested. See Figure 3 for a snapshot of the report I got back from Rhomar Water.

I knew we needed a water softener, but I won’t be using softened water for my system — and I sure won’t be using the existing tap water. I considered buying a deionizing water cart, but it didn’t make sense for me because I’m no longer in the field, and I’d never see a payoff. I ended up buying a 55-gallon drum of deionized water for a fraction of the cost; it’s more than I need. For the clean and flush of the system, I will use tap water and then pump in the deionized water along with a conditioner for the final fill.

This approach gave me peace of mind because I prefer protecting my investments and doing things the right way. If you dismiss the water quality recommendations by the boiler manufacturers clearly stated in the installation instructions, there will be a price paid for it. On top of that, I added magnetic separators and magnetite filters to protect my ECM circulators and other components.

Here’s one I feel strongly about and is contrary to what most boiler manufacturers will accept. However, if you look at pipe manufacturers’ recommendations, you’ll get a different story. You already know where I’m going with this, don’t you? Yep, the generally accepted use of PVC pipe to vent the byproducts of combustion on a modulating-condensing boiler.

What you will typically see in the boiler’s installation manual is something along these lines: “Use only approved stainless steel, polypropylene pipe, CPVC or PVC pipe and fittings.” The key word here is ‘approved.” Whose approval? It seems somewhat vague, but look at what a major pipe manufacturer has to say: “Always install/use pipe or fittings as specified by the appliance manufacturer's installation instructions to vent appliances.”

Again, is either saying specifically that Schedule 40 PVC pipe is OK to use to vent a mod-con boiler? I’m not seeing it, are you? The buck seems to be being passed back and forth here. There are some states where it is against code, and good for them. I base my choice on what I’ve seen in both residential and commercial boiler rooms: PVC pipe that has melted, sagged, discolored brown or purple.

Why would you even take the chance of putting someone else’s life in danger? Not me; I use polypropylene manufactured and approved for this specific application.

Near-boiler piping

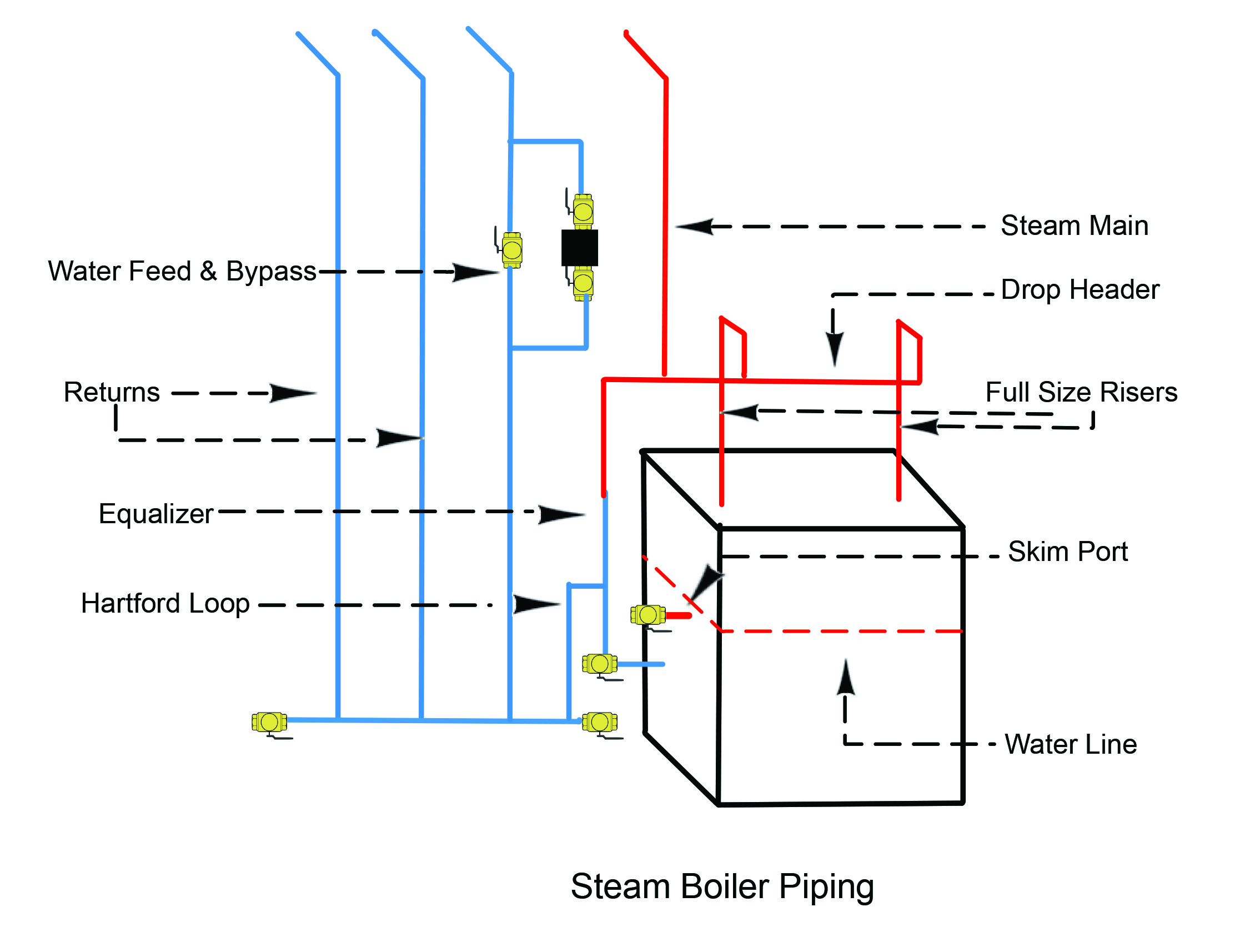

I’ll be the first to admit I don’t have as much experience in steam near-boiler piping as I do in near-boiler piping for a modulating-condensing boiler. But in truth, there’s less to know. Besides pipe sizes and the number of risers, the near-boiler piping shown in Peerless and Burnham steam installation manuals is the same as the near-boiler piping in Smith and Weil-McLain boilers (see Figure 4).

Here’s what I’ve been taught to keep myself out of trouble:

• Use full-size risers; never reduce the pipe size.

• Use the manufacturer’s recommended number of risers.

• Same goes for header size and equalizer sizes; follow the manufacturer’s instructions.

• A reducing 90-degree elbow from the header to equalizer is recommended; don’t use a bushing.

• Offset the risers into the header with 90-degree elbows to allow movement.

• 24 inches is needed between the top of the boiler and the bottom of the header, with dry steam as the goal. Using a drop header as shown allows for drier steam.

• The steam mains must connect between the last riser and the equalizer.

• Make sure the Hartford Loop is below the waterline.

• Make sure the returns tie in below the waterline.

• Vent the mains fast and the radiators slow.

• Allow for skimming and flushing with valves or boiler drains. I prefer to use full-port ball valves with a hose adapter instead of boiler drains.

• When you see the “A” dimension in the manual, pay attention to it. Do this right and you avoid water backing up into the dry returns.

Recently, I’ve seen at least three boilers piped with the mains connected between two risers. The net result is steam from each riser crashing into each other and slowing it down, as well as water carryover into the mains — not good. I’ve also seen the end of a header piped into the bull of a tee with the top run of the tee going to a main and the bottom run of the tee dropping into the equalizer. Saying we’ve always done it that way doesn’t make it right. It might even make it more wrong, yes?

There’s more. There’s always more.

Recently, I read this from a contractor: “We installed a new boiler for a customer, and now he’s complaining that he can’t get the house above 60 F in this cold weather. He’s not happy.” One responder told the guy that he may need more baseboard on the lower level because of the amount of glass.

Questions from the group followed:

• What size is the new boiler?

• What did you get on the heat loss load calculation of the home?

• How does the heat loss match the heat emitter’s output?

Once the contractor said he didn’t conduct a heat loss, the conversation went south, as you might expect. Here are my two cents: If you get the job, do a heat loss load calculation. For most houses, it won’t take long at all. You do not want to find out after the fact that you sized the equipment wrong by using an inexact rule of thumb. Run the numbers, trust the numbers.

Most of the stuff you’ll read in manuals, you’ll already know. That one thing I’m looking for may separate me from others not taking the time. You would think that reading has already been banned or, at least, the reading of installation manuals. It hasn’t. No manuals are being burned either, so let’s start reading them.